ROUD 83: Archie o' Cawfield

AKA: The Bold Prisoner, The Three Brothers, Bold Dickie, Billie Archie, The Bold Archer, Billy Broke Locks, Escape of Old John Webb, Johnny Ha'

This is one of those songs that has, over a few centuries of reworking and adaptation, evolved into several quite disparate strands. In its original form, it is a retelling of the previous entry in the Roud Index, "Jock o' the Side", with the names changed. This may have been documenting a similar event lost to history, or possibly an attempt by less notorious characters to inveigle themselves into a dramatic storyline for the purposes of self-aggrandisement. Either way, there seems to be no historical account involving a Johnny Hall being broken out of prison by an Archie o’ Cawfield, although there is a brief mention of a “John Hall of Newbigging” among a list of clansmen operating as border reivers in 1597, and “Cawfield” is a recognised family name and geographical area near Hadrian’s Wall. One theory is that Archie o’ Cawfield in fact refers to Archibald Armstrong of Mangerton, the last chief of the mighty Armstrong Clan, who was executed in 1610.

Like many songs of the homeland, this ballad made its way to the US with settlers in the 17th century, and in 1730 was repurposed to tell the tale of one John Webb from Salem, Massachusetts who was, according to the song, freed from jail with the help of a man called Billy, who was good at breaking locks (a skill of which we are frequently reminded in its insistent chorus). There was a real life John Webb (or John Webber, it’s not clear) who was imprisoned at that time for printing obsolete bank notes as a form of protest, but it seems he did not escape, he was released without charge. But still, the song (either under the title “Billy Broke Locks” or “The Escape of John Webb”) became popular in some parts of the US folk revival, and still seems to be relatively popular among Civil War recreationists and the like today. Although it wasn’t that the original version was erased from memory; earlier versions with the Scottish content still intact did persist, with a version called “Bold Dickie” found in Massachusetts in the early 20th century.

Back in the UK, it re-appeared as a broadside named “The Bold Prisoner” in London in around 1804, and subsequently another version that seems to have evolved in the South of England at some point as “The Bold Archer”, which appears to be an anglicised abridgement and combination of several variations of the ballad, including The Bold Prisoner broadside, and two other Scottish versions named “The Three Brothers” and “Billie Archie”. This latest stage of evolution seems to have settled into being the most popular for modern singers on this side of the Atlantic.

Music

I have tried to order the playlist to reflect the ballad’s evolution described above. I’ll give some examples here to show the range.

Archie o’ Cawfield

In 2001 Mike Yates recorded Duncan Williamson singing “Archie o’ Cawfield”, which seems to be the most authentically Scottish recorded version, and closest to those collected several hundred years ago.

I also found this lovely instrumental version:

Although despite being titled “Archie O’Cawfield”, his seems to be the “Bold Dickie” melody collected in Massachusetts in 1939.

Billy Broke Locks/Escape of John Webb

Here’s John Roberts with a representative version, with a short summary of the song’s history as an introduction.

Burl Ives also has a 1963 recording, also with an introduction on the album, a sadly obsolete recording technique today.

Bold Archer

This is has been embraced most comprehensively by English singers, seemingly deriving from this 1965 recording of farmworker Harry Cox, who had been singing it since the 1920s.

This was followed up by a slew of revival versions, including John Kirkpatrick’s, sung here with great gusto in the mighty Brass Monkey band:

Another album which also includes speech from the artist is actually a recording from the erstwhile 1970s BBC radio programme Folkweave (some interesting reminiscences about the programme on the Mudcat website here). It seems the master tapes from the series were lost, but a few vinyl albums remain. One of which contains the late great Tony Rose singing his version of Bold Archer, including a characteristically funny introduction:

Hard to find versions

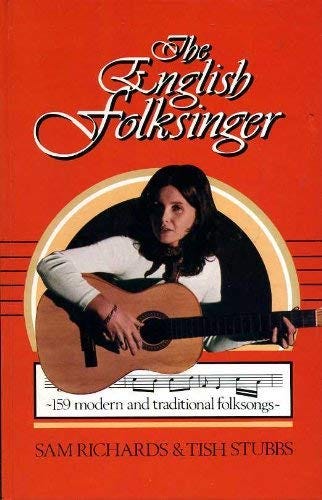

In 1979, Sam Richards and Tish Stubbs wrote a book of traditional song arrangements called The English Folksinger:

In an early attempt to emulate the future runaway success of Sing Yonder, they also produced a now difficult to find album, including an unaccompanied version of “Bold Archer”. There is a clip below, full version after the break for paid subscribers.

The sleeve notes are as follows:

“This is a rare version of the ballad Child called “Archie o’ Cawfield”. Harry Cox, a truly great traditional singer, had been singing it to folk song collectors ever since 1920 when he was a young man. His repertoire was prodigious. Even so, it was more than surprising that he should pull this one out of the hat in his last years.

It’s much abbreviated in comparison to those in Child. Nevertheless, the story’s all there, and it sings well.”

Another version of this song can be found on Ollie King’s now rare 2004 album “Gambit”. Again, clip below, full version after the break for paid subscribers.

Ollie says of his version:

“A song I first heard by Brass Monkey, which comes from the singing of Harry Cox of Norfolk. Here, I’ve compiled the lyrics from various sources, including my own head.”

Sources

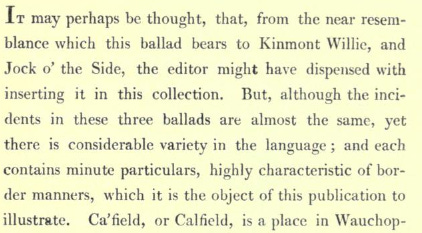

In Walter Scott’s 1803 Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borders, Scott gives some good reasoning why the three very similar “prison-break” ballads (of which this and the previous ballad are two) have been kept separate.

In 1828, Peter Buchan published his Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland (a long way from the border region, presumably showing the song’s popularity) which included a version titled “The Three Brothers”. His notes are as follows:

It seems that William Motherwell was not so great at attributing his collectors, but Buchan seems very gracious about it here.

A good account of “The Bold Prisoner” broadside which seems to be the genesis point for the popular English “Bold Archer” variation can be found in US scholar Frank Bryant’s 1913 book “A History of English Balladry”. In his introduction to the broadside, he gives an interesting account of how he dated the broadside by using some salient features of the second ballad on the sheet, then goes on to describe the ballad, and give a good example of how often these long ballads came to be shortened in the broadside era, ie. for reasons of space - a practice with which we are very familiar here at Sing Yonder Towers.

The broadside itself can be seen in an anthology of broadsides from the Pitts publishers here.

Finally, what little is known of the history of the “Billy Broke Locks” US version can be found here.

Draft pages, audio guide, and two full rare versions

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.