Like the previous ballad, this is mainly the story of a prison escape. The “Jock o’ the Side” moniker refers to a John Armstrong of Mangerton, Liddesdale (not the same as the Johnnie Armstrong in a previously discussed ballad, but there’s a possibility he was a clan relation) who was captured during a raid, and later sprung free by exiled Englishman Hobbie Noble and others. As usual, a lot of the details of the escape given in the ballad can’t be verified from the fragmentary information given by contemporaneous anonymous accounts, but it all sounds relatively plausible.

Music

Here’s a very short playlist for this rare ballad, the most notable being Ewan MacColl’s contribution:

There is also a recording of one of the melodies, from piper Gordon Mooney, available here (last tune in the set):

Sources

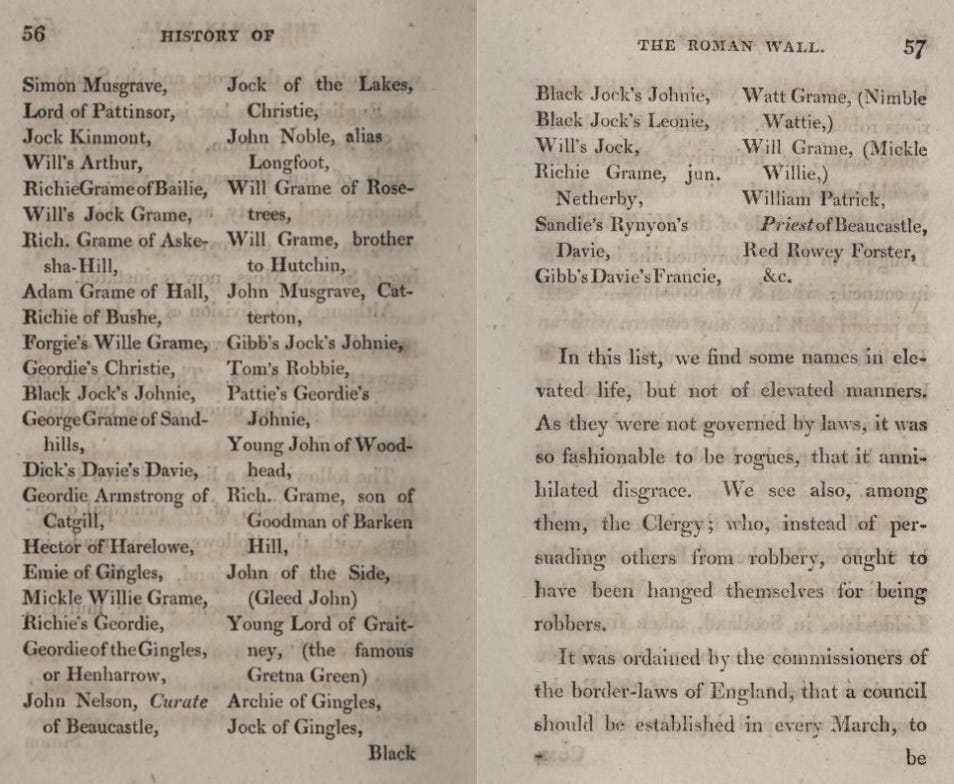

In 1550 the Bishop of Carlisle received a list of active marauders, among which we find the first mention of “John of the Side”.

What “the Side” referred to, which side, and the side of what, is not recorded. but I did find mention of a place in Liddesdale near Mangerton called “Syid” which could be a contender, especially considering the alternating spellings of “Side” and “Syde” in the literature. I also found this webpage which might contain some useful information, but frankly after about a minute of looking at it, it made my head hurt so I gave up.

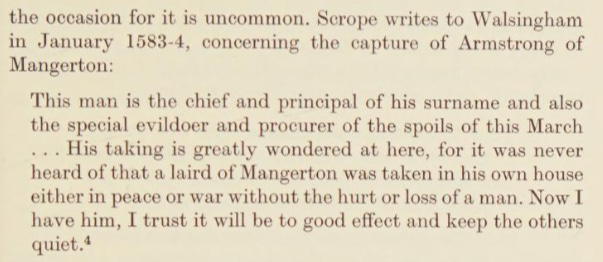

Another useful historical account comes from Thomas Percy, 7th Earl of Northumberland, who led the 1569 “Rising of the North”, a failed attempt to install Mary Queen of Scots on the throne in place of Queen Elizabeth I. On one of his incursions into Scotland, Percy took refuge in the house of a “John of the Syde” in Liddesdale. He didn’t have a great time, however, describing John’s house as “a cottage not to be compared to any dog kennel in England” and John himself “the greatest thief to ever have lived”. This was sadly borne out when John’s men robbed him and his wife of all their possessions.

Finally the poet and historian Sir Richard Maitland mentioned above wrote and collected a suite of ballad poetry about the thieves of Liddesdale from that era, including some useful information about Armstrong of Mangerton. It is neatly summarised by James Reed in his 1991 “Border Ballads”.

Reed goes on to discuss the ballad at length, and is well worth reading for a great summary of all we know about it, and some of its stylistic features.

For an earlier and more succinct look at things I turn to my old friend, the dashing Frank Sidgwick, whose pithy summaries always seem more contemporary than their 1908 date would suggest. I suspect he might be a time traveller. I mean, look at the moustache. Pretty sure I’ve seen him in an ITV period drama at some point:

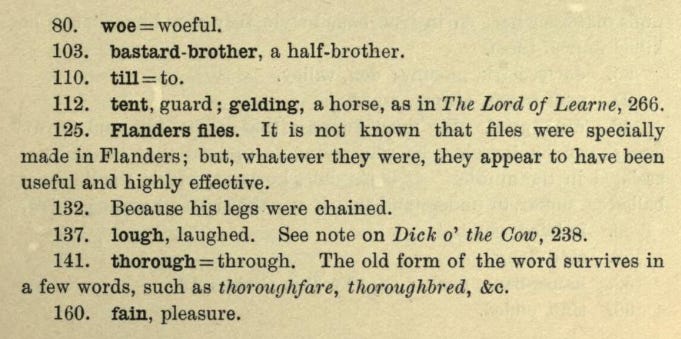

He also includes some useful glossary notes.

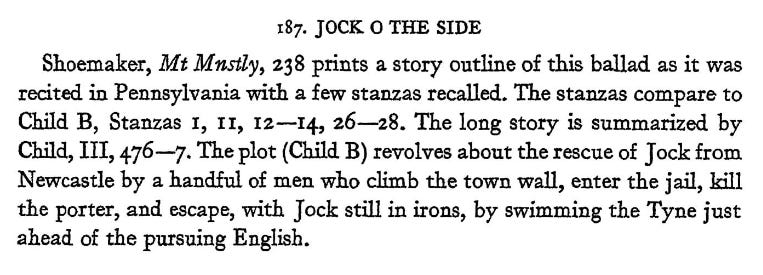

It’s no real surprise when ballads such as this appear in America. I imagine tales from the homeland of daring, adventurous and morally ambiguous folk given to theft of innocent natives were popular around the pioneering immingrants’ campfires. Here’s Tristram Coffin’s summary of the ballad as it was found in Pennsylvania:

As a sidenote, this ballad is rare in that we have evidence of its existence before 1600, as it is cited for its melody to be used as a tune of another ballad, in a manuscript dated no later than 1592. This from “Old English ballads” by Edward Hyder Rollins (1920):

Bonus tourist information

If you find all this border reiver history interesting, and you are planning a trip to Scotland at any point, why not take in the Border Reiver Trail:

Draft pages and audio guide

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.