ROUD 63: Johnie Scot

AKA: Johnie Buneftan, Johnny Scot, Johnnie Scott, John the Little Scot, Love Johnnie, Mcnaughtan, Young Johnny Scott

This is one of those ballads where a schism seems to have occured early in its life, between two seperate strands. Child collected 19 versions dating from the 17th century, but only one known broadside - these can be found on the Bluegrass Messengers site here, with. The familiar central theme is the same for both; a protective father disapproves of his daughter’s lover, similar to the more popular “Willie O’ Winsbury”, except in this case there is a fight that wins over the father, rather than the attractiveness of the suitor.

Music

It has been collected from a few source singers but very few contemporary artists have taken it on, leaving us with little to listen to today. As well as a beautiful setting from Irish singer Susan McKeown, and a single verse from 1950s American folksinger Paul Clayton. there are a number of interesting source recordings available on the Youtube playlist, my favourite of which is the 1971 recording of Mary Baylon of Ardee, County Louth, Ireland, made by Seán Corcoran.

Seán’s singing of the ballad follows this in the playlist, and it’s a really interesting and immediate little microcosm of a ballad being passed down from one generation to the next.

Several more recordings from Bell Duncan (see the entry for Fair Mary of Wallington for the little we know of her) under the title “Love Johnnie” made by James Madison Carpenter (see below) in the 1930s can be found in this record on the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (click “Show all media items” to reveal the audio clips). Unfortunately they are of very poor quality.

Another version I found on Soundcloud comes from Scottish traditional and classical singer Leona Evans, AKA Leona Mason.

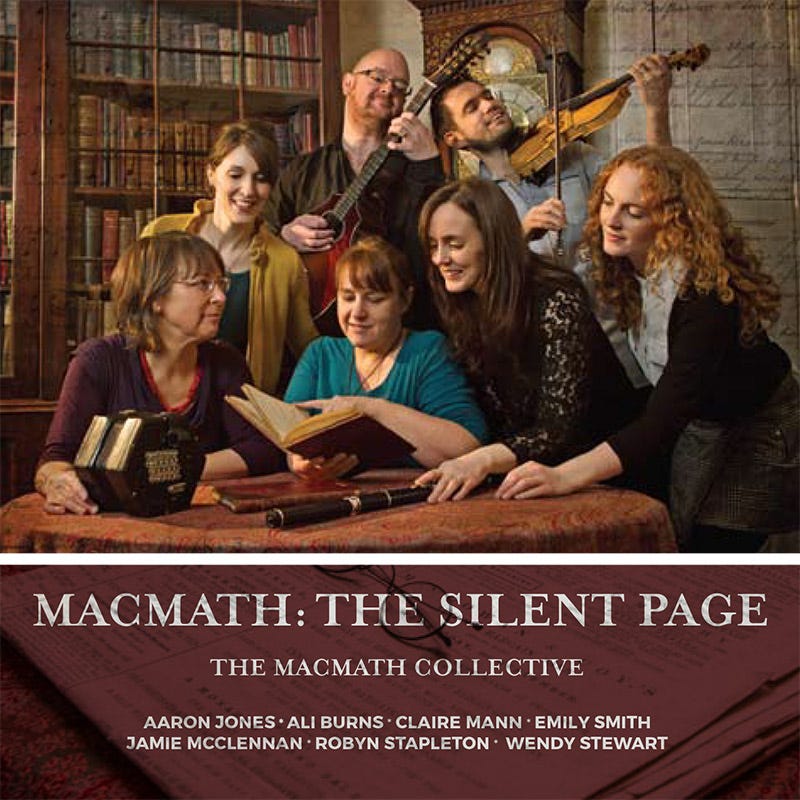

Finally, there is The Macmath Collective, a group of musicians and folk song researchers brought together for a special project by The Dumfries and Galloway Folk Festival in 2015, with the aim of working with songs collected by William Macmath (1848–1922).

Macmath was from Galloway and helped Francis Child with his collection by tirelessly collecting song manuscripts from the area over the course of 30 years; Macmath is certainly one of the reasons that Scottish songs are so strongly represented in Child’s collection. Many of the ballads he found were fragmentary and unpublished, and the group’s main objective was to lift the songs off these lost pages and turn them into recorded music. You might have gather that this is something I am quite passionate about, and I’m so glad this song has led me to them. The album can be purchased here - it’s really well done, clearly a fine group musicians at the top of their game. If you are interested in Scottish music, and even if you aren’t, you won’t be disappointed. Here is a small clip of their version of Johnie Scot.

See also this Jstor article from 1956 discussing the importance of Macmath’s work to the Child collection, and also the biographical note by Frank Miller, which can be found in the appendix to Macmath’s posthumously published biography of The Gordons of Craichlaw, which can be read online here.

James Madison Carpenter

Thanks to his recording of Bell Duncan singing “Love Johnnie”, this is a good point to introduce James Madison Carpenter (1888-1983), a Harvard scholar of traditional song who spent six years travelling around Britain collecting songs on his dictaphone in the 1930s. His collection is of paramount importance as not a great amount of collecting was going on in the inter-war years, and he almost certainly collected songs that would have been lost otherwise.

This from the EFDSS page on Carpenter (which also includes an extensive audio interview with him in 1972, at 84 years of age) is a great introduction his work.

If you would like to read in more depth about Carpenter’s life and work, this article from Jstor by Julia Bishop is well worth reading.

Some sources

The brilliant ballad anthologiser Frank Sidgwick (1879-1939) nails it, as usual, succinctly summarising a couple of the suggested “real life” origins.

The Breton ballad can be found here, if you enjoy reading stories about naked men fighting.

A fuller account of the supposed fight between Macgill and Balfour can be found on this page, and a mild refutation of the Italian story shortly after - I have extracted the relevant passage here:

About the close of the seventeenth century a fatal duel occurred between Sir Robert Balfour of Denmylne, and Sir James Macgill of Lindores, who were near neighbours and intimate friends. Sir Robert was a young man in his prime; Sir James was much more advanced in years. Attended by their servants, they had both gone to Perth on a market day, when Sir Robert unfortunately quarrelled and fought with a Highland gentleman on the street. Sir James came up at the time and parted the combatants. In doing this, it is said, he made some observations as to the superiority of the Highlander, which offended Sir Robert, who, chafed and angry, offered next to fight his friend. They returned home together on the evening of a long summer day. When at Car-pow they dismounted, gave their servants their horses, and, ascending by the road a considerable way up the hills, they stopped at a spot on the slope of the Ochils where a small cairn of stones, locally known by the name of Sir Robert’s Prap, was afterwards raised to commemorate the event. They there drew their swords. A shepherd, who was sitting on a higher part of the hills, is said not only to have seen what took place, but even to have overheard what passed between them. It is said that Sir James Macgill, who is alleged to have been by far the more expert swordsman of the two, made various attempts to be reconciled to his angry friend, and even after they were engaged, conducted himself for a time merely on the defensive. But from the fury with which Sir Robert fought, he was forced to change his plan, and to attack in turn. The consequence was that Sir Robert was run through the body, and died on the spot, when Sir James mounted and rode off, leaving his corpse to the care of the servants. It is added that Sir James immediately afterwards proceeded to London, where he obtained a pardon from King Charles the Second. Mr. Small, in his Roman Antiquities, tells a foolish and very improbable story of Sir James being obliged by the king to fight an Italian swordsman then in London, who had previously acted the bully, but who also fell beneath the skilful arm of the Scottish knight. (Leighton’s Hist., of Fife, vol. ii. p. 178.)

William Motherwell (1797-1835) has plenty to say about this ballad, using it as an opportunity to vent on what are clearly his trigger points. First he has a pop at collectors who dare to change the ballads they find.

The “more of this” he alludes to at the end of that passage seems to be referring to this savage footnote on the next page, in which he casts some quite outrageous aspersions on the air-quoted “ingenious hands” of ballad-publishers, describing them as “Impudent, Dull-witted, Ignorant, Conceited, Trashy, Poetasters and Forgers”:

How dare you, William. I am *not* conceited.

Next he muses about proper names in ballads, how they vary, and what it all might mean. Good luck with that one, Will.

His final summation:

I agree it’s a fine swashbuckling song, where the indomitable spirit of youth prevails over the old inflexible ways of a generation obsessed with power and heredity. I’m not sure what sort of gender-based point Motherwell is trying to make by describing source-singing women as “ancient” and the men as “time-crazed” - is it that men are driven mad by age whereas women are not? If that were the case, it would be a surprisingly feminist notion for the time, and don’t get me wrong, I’d be very happy if it were, but based on my previous experience of these songs and the men who wrote about them, it seems unlikely.

And based on my previous experience as a man getting older, yes I am going slightly time-crazed, but that might partly be to do with the Roud index.

Draft pages and audio guide

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.