ROUD 59: Fair Mary of Wallington

AKA: The Earl of Livingstone, The Fair Maid of Wallington, Lady Maisry, Wallington

Another rarely heard but absolutely beautiful song, brutally explicit, yet exquisitely sad. The plot is fairly well summarised in the Wikipedia article.

Music

Here is the short Youtube playlist.

This rather timeworn snippet is the earliest recording, sung by farmhand Bell Duncan in 1932. (For a bit more about Bell, keep reading.)

The only modern recording to have ambitiously taken this rather sparse melody and created an arrangement around it is Chicagoan folk veteran Phil Cooper.

(Note: I’m almost certain that the Youtube video above has been algorithmically attributed to the wrong Phil Cooper; the correct one is linked above. If I’m wrong, apologies to both Phils.)

For me, nothing matches the sadness evoked by the brilliant Cath and Phil Tyler in their version from their masterpice The Ox and the Ax. This version filmed in a tunnel in Newcastle is great. Looks like my kind of gig.

Their melody sounds derived from the June Tabor a capella version, which she apparently learned from the great Maddy Prior. Where Maddy Prior found it, I do not know, and Maddy was unavailable for comment.

In addition, here is a different take from Sheffield stalwarts of the folk scene Graham and Eileen Pratt:

Also, Corinne Male, a brilliant singer and fount of knowledge (and who I’m delighted to have met at a Royal Traditions night in Sheffield) performs her own variation, under the title “Maisrie of Livingstone” on her album “To Tell the Story Truly”, only available here.

I’m sure, especially now I have given you that unequivocal recommendation, she won’t mind if I include the following small clip.

Trevelyan family links

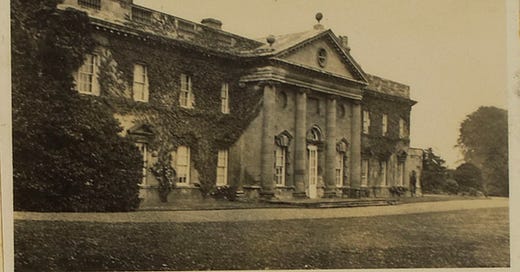

Wallington Hall stands on the ruins of an old castle. This is the supposed site of the ballad. Or at least, according to this George Trevelyan family memoir from 1905.

Experienced travellers on the ballad scholarship road will not be surprised to hear that no historical figures fully match up to the events of the song (although Elizabeth Gordon, Lady of Livingstone (1596 - 1643) has been suggested, but in words of Child “the characteristic particulars are wanting”). However, across the water, there *might* be a chance at historical provenance...

Pontplancoat (Sp?)

Most sources talking about Roud 59 refer to “Pontplancoat” as an analogous ballad originating from Brittany, about the misfortunes of an apparently fictional nobleman as successive wives die in childbirth. It’s interesting to see how the story changes when not written from the point of view of the woman - it’s impossible to feel any sympathy for this lord’s “woes” - the women are simply a sideshow to the compared to the real pain and suffering felt by the noble Breton and his quest for heirs. You can read several versions in this translation, but for all you readers of early Breton, here is the original with a parallel version in French.

I couldn’t find any mention of the name “Pontplancoat” other than in references to Fair Mary of Wallington, until, via this useful page on the Breton oral tradition, I found it spelled “Pontplencoat” - which is indeed a town in Brittany. And from there found a possibly sustainable suggestion that the song could have referred to Jean de Penhoat (or Penhoët) who was "Admiral of Brittany" in 1401, and of whom little is known other than that he had at least two wives. Also the practices surrounding the birth described in Fair Mary of Wallington and Pontplencoat match up with what was going on in the early 15th century (see below).

Lots more, including the original Breton tunes and a possible link to Shakespeare, can be found in the translation of this page.

Scobs/Scopes/Gags and caesarian sections - trigger warning: contains some gory childbirth-related medical content

This verse in the original:

Her daughter had a scope

into her cheek and into her chin,

All to keep her life

till her dear mother came.

has aroused some discussion, and possibly helps us date the ballad. To summarise, from Frank Sidgwick’s excellent “Popular Ballads in the Olden Time”:

In the Scottish ballad, a 'scope' is put in Mary's mouth when the operation takes place. In the Breton ballad it is a silver spoon or a silver ball. 'Scope,' or 'scobs' as it appears in Herd, means a gag, and was apparently used to prevent her from crying out. But the silver spoon and ball in the Breton ballad would appear to have been used for Marguerite to bite on in her anguish, just as sailors chewed bullets while being flogged.

Further to that, it should be mentioned that placing items in the mother’s mouth was also used in the early days of caesarian section, in the belief that maintaining the woman’s airway would somehow help preserve the life of the child in the womb. More here, in Italian (probably give it a miss if you are squeamish or have recently had a traumatic childbirth experience).

A much longer and more dispassioniate discussion of this aspect of the ballad can be found in this Jstor article.

Bell Duncan

The only source recording we have of this song is the very scratchy and barely listenable wax cylinder recording made by James Madison Carpenter in 1932. The singer was Aberdeenshire farmhand and housekeeper Bell Duncan (1849-1934), who was according to Carpenter his “stellar informant for ballads and songs, most of which she apparently learnt from her mother. Carpenter claimed that she gave him 300 ballads and songs (including 65 Child ballads), texts and tunes”.

The audio recording with Madison’s original typed transcription can be found here in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library.

Not a great deal more is known about her life other than the fact she had three children, and she died in 1934 at an admirable 85 years of age. Julia Bishop wrote an article about her musical style in the academic anthology “Folk Song: Tradition, Revival, and Re-creation” which is not available online, but if you’re passing the library at EFDSS in Camden, they have a copy.

Draft pages and audio guide - plus a sneak preview of the Sing Yonder album!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.