ROUD 88: Lord Delamere

AKA: Lord Delaware, The Long-Armed Duke, Devonshire's Noble Duel with Lord Danby in the year 1687

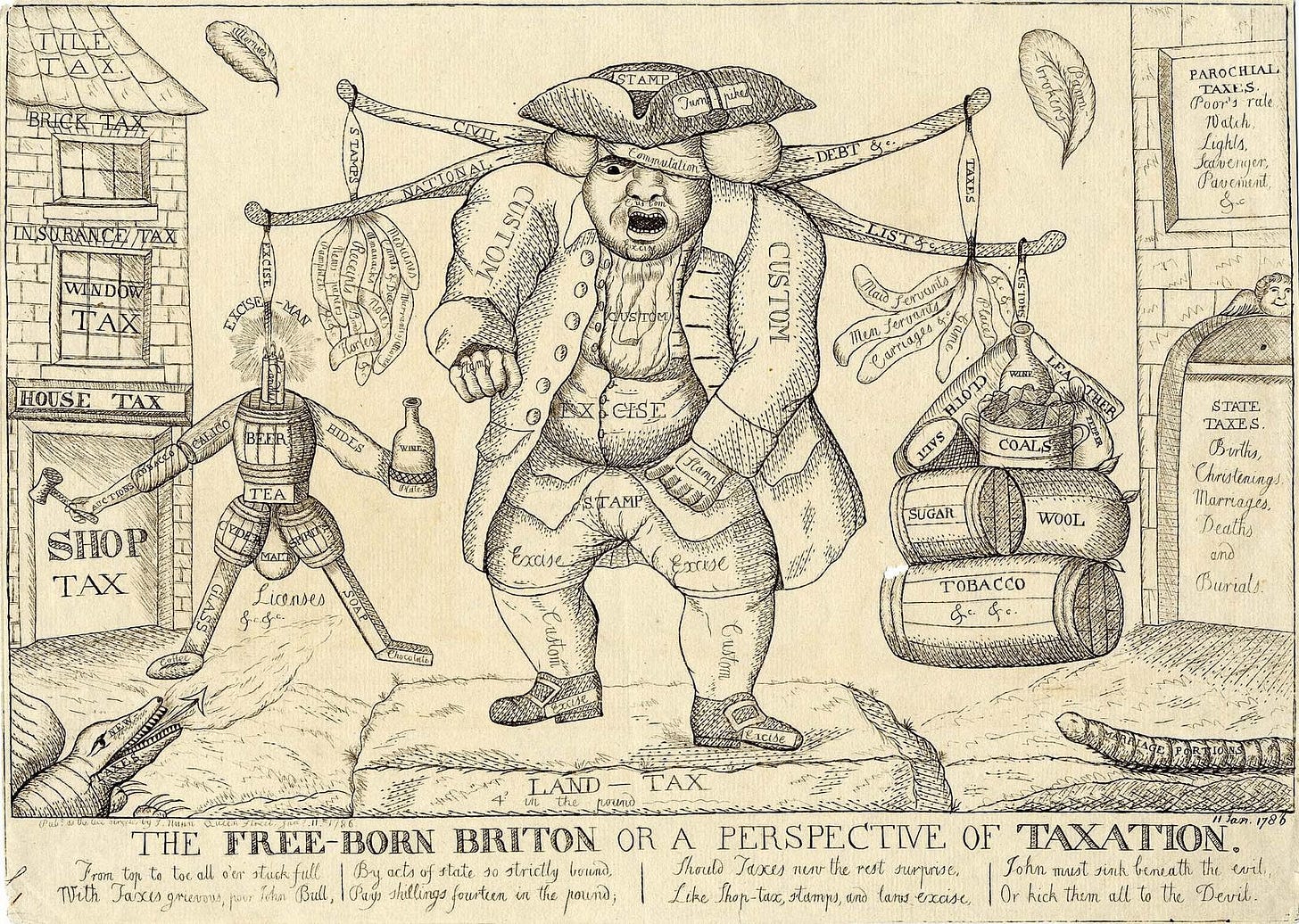

One of the joys of researching traditional songs is that we are sometimes given a useful insight into wider social concerns of the time. The 17th century was a turbulent era, as the English Civil war had been very expensive for the crown, the cost of which had increased as a result of the conflict by about a third. So money needed to be raised, and of course the highest powers in the land decided it should be the poorest in society, mostly the agrarian peasantry of the time, who should bear the brunt of this cost via punitive new taxes. This led to uprisings among the general populace, and a few notable figures in parliament also bravely spoke out, one of whom was Henry Booth, first Earl of Warrington, who was made Lord Delamer (an alternate spelling of Delamere which seems to be interchangeable) who appealed emotively to King James II in opposition to his reforms, and was later involved in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 which installed William of Orange as King.

As usual the central incident of this ballad - a sword duel between the Duke of Devonshire (an experienced military man who supposedly fought on Delamer’s behalf) and an unnamed French (or in some versions, Dutch) lord is not recorded in history, nor is there any record of it happening anywhere else. The closest event to this is a report that a disagreement between the Duke of Devonshire and Colonel Culpepper culminated in Devonshire striking Culpepper with a stick in the drawing room at Whitehall on the 24th of April, 1687.

It should be no surprise to regular readers that ballad writers are somewhat prone to exaggeration. However, the idea that a government official would approach the king with a proposal to kill all the poor rather than have them slowly starve is surely an indication of the powerful feelings at work in society as a whole. And of course these ideas of inequality and the unjust burden of taxation on the poor are still very relevant issues today.

There are a few variations of this rare ballad, one of which was found in Glasgow (but with a mention of Lincolnshire in the ballad), with Lord Delaware being the title given, although that is not a peerage that exists. It does however also mention Lord Willoughby, a title often connected with that area. It was also found in Derbyshire, and several of the Devonshire family seats can be found in that area, the most well known being Chatsworth House, although the family also own tracts of various other surrounding counties, including Lincolnshire. Personally I would sit on the fence and say the ballad probably originated from the central region of England and leave it at that.

Music

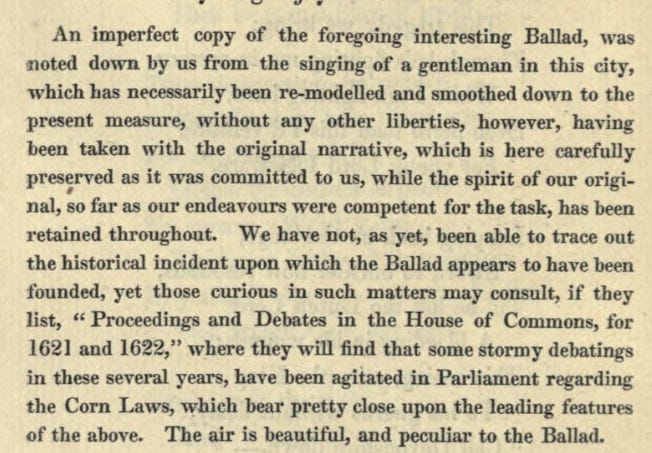

This is historically an unpopular ballad, with no record of it having been sung beyond the mid 19th century, until very recently. Also, no tunes have been collected from its existence in the wild at that time or any other, the nearest being the somewhat frustrating admission that it was “beautiful, and particular to this ballad” (see Lyle’s reference in Sources below).

Thankfully, folk musicians are a resourceful and inventive bunch, intrigued by the prospect of venturing down some of the less well worn corridors of our musical heritage. So we have a few recent attempts to drag this ballad back into the light, some of which can be found on the Youtube playlist. One such is from friend and previous Sing Yonder collaborator Helen Lindley, whom I commissioned to write two arrangements for Sing Yonder vol. 7, namely Willie o’ Douglas Dale and Tom Potts. She continued her quest for unsung ballads from the Child collection, and this is an example of her continued dedication to the cause:

In a first for Sing Yonder, I interviewed Helen, and this can be found after the paywall of this post. We discussed Helen’s entry into folk music and folk’s changing place in the entertainment firmament, the idea of lost songs generally, how she approaches them, and briefly touch on this ballad towards the end.

Another interesting take from the playlist comes from the US, and Paul Rippey, who gives us his satirical rewriting of the story, in a light hearted Dylan-esque style.

As anyone who knows me knows, I am always intrigued and delighted by folk song when it appears outside the usual environs of the folk club or singaround, and makes it into more esotoric or popular musical realms. There is an excellent example of this from Jack Dean and Company, who describe themselves as “a magpie's nest of folk, indie, hip-hop, post-rock and midwest emo”. Their take is a menacing and righteously angry one; a perfect demonstration of how traditional song can be used in a modern context.

I reached out to Jack to get his thoughts on the ballad, and some information about why he chose to record it, and he gave us this helpful insight:

I'm a writer, composer and songwriter based in Exeter. I've been interested in the folk canon for a while. I love the idea of a song being a thing that lives in the public domain that anyone can iterate on, an idea that's been lost a bit in both the classical and pop traditions in the era of Intellectual Property. Coming from a hip-hop background musically, there's a lot of overlap in my mind between folk re-iteration and sampling. I started combing the (slightly more compact than Roud) Child Ballads index for something with a leftist or anti-authoriarian bent, and came across Delamere. Obviously the politics of the 1600s don't map directly onto our own - a dispute between two Lords over taxes is hardly akin to Occupy. But there is something so fantastically swaggering about walking up to the King and saying " Listen bro, if you hate poor people this bad just send me in to kill them, because that's what your policies are gonna do anyway". And like all good folk songs, it tells a great tale, with twists, turns and reversals. The last stanza has a fantastic portent-of-doom quality as well. It really set things up on a fun, explosive note to close the album the song is on.

I rarely offer my opinion on the merits of one ballad or another; I prefer to view them as a repository as a whole, but I think this is a good and unfairly overlooked one. It’s central theme of justice for the poor (a fairly rare occurence in Child ballads, which are often skewed towards the romantic affairs of the upper classes) mixed with the drama of the fight, the intrigue and deception, and some striking imagery, especially the lines

I'll take them down to Cheshire, and there I will sow

Both hemp-seed and flax-seed, and hang them in a row.

'It's better, my liege, they should die a shorter death

Than for your Majesty to starve them on earth.'

The idea of a politician offering to kill their constituents rather than have them suffer long painful death by malnutrition is a stark one. The inclusion of the reference to hemp and flax, crops traditionally grown to make rope and fabric, is particularly poetic; using the idea that the agrarian poor would indeed be killed by the products of their labour.

Sources

Child’s commentary on the ballad can be found here: http://bluegrassmessengers.com/207-lord-delamere.aspx, and here are the Roud index entries.

The earliest record we have of this ballad comes in Thomas Lyle’s snappily titled “Ancient ballads and songs, chiefly from tradition, manuscripts, and scarce works”. Little is known of Lyle’s life, other than that he was a Scottish physician based in Glasgow, but he somehow came across this ballad, which is unapologetically English. Perhaps he was attracted by its anti-authoritarian message, a theme of so many Border ballads in which he would have been steeped. He had a fairly complete version, which he admitted to “smoothing down” a little, though preserving all the elements of the story and the spirit of the song he was given:

The idea of an unnamed “gentleman” singing a ballad about English politics in Glasgow in the early 19th century is a scene we will just have to imagine.

The long running journal Notes & Queries, which has published short articles on literature and history since 1849, ran this short piece in 1852 which contains some interesting (if predictably futile) attempts to attach the events of the ballad to verifiable history - it could be the origin of the Devonshire/Culpepper theory mentioned above.

This, from “The Ballads and Songs of Derbyshire” (1867), gives us some extra information that paints a vividly bizarre physiological picture explaining the “Long-Armed Duke” title that is used in one version.

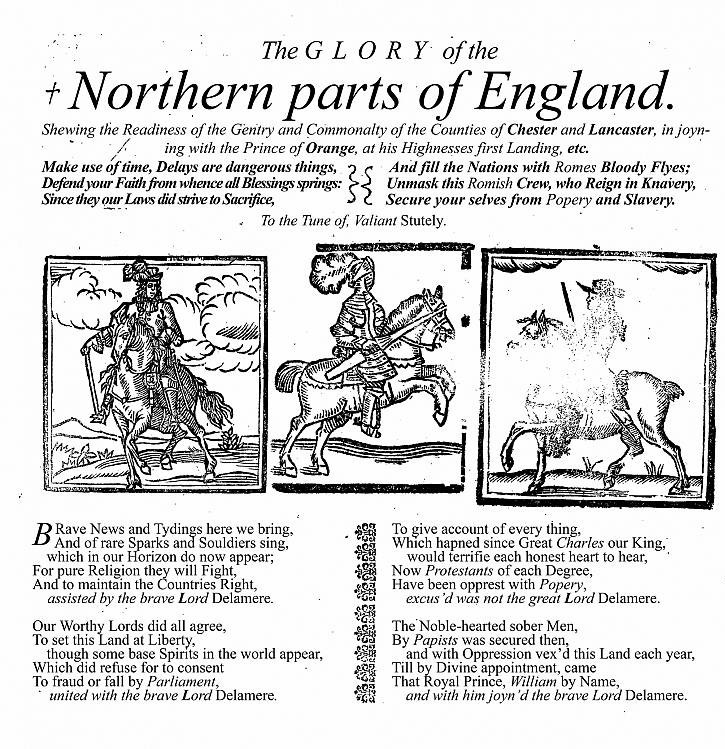

This is not the only ballad that concerns Lord Delamere and his lifelong quest to quash tyrannical inequality. This celebratory broadside from 1689 recounts Delamere’s assistance in ousting the Catholic James II in favour of William of Orange.

Robert Bell in his 1857 “Ancient poems, ballads and songs of the peasantry of England” makes a valiant attempt to connect this ballad to an earlier proponent of justice for the lower working classes, Thomas De la Mare (c1377) who under the reign of Edward III and subsequently Richard II:

“protested against the inhabitants of England being subject to ‘purveyance’, asserting that ‘if the royal revenue was faithfully administered, there could be no necessity for laying burdens on the people”

Apart from his admirable protestations against class injustice, and the similarity of the name, there is no record of the other events of the ballad happening during De la Mare’s lifetime, but it’s easy to see how this character might have been adapted to 17th century concerns.

Finally, if all this talk of taxation changes is what gets you going, this useful article on the history of the English fiscal system is a good primer.

Draft pages, audio guide and an exclusive video interview with Helen Lindley

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.