ROUD 87: Waly Waly

AKA: Jamie Douglas, The Water is Wide, Cockleshells, Lady Douglas and Blackwood, The Laird o Blaekwood

After a long stretch of ballads concerning shameless thievery and swashbuckling rogues having their heads chopped off, it comes as something of a shift of gear to come across this sentimental love ballad. But that’s the unpredictable beauty of tackling the Roud Index in this brutally numerical way.

Roud’s index entry contains a wide variety of songs; most are a popular song with general themes of love and loss (the “Waly Waly” versions), but there is also a Scottish historical narrative ballad telling the story of the rejection of Lady Barbara Erskine by her husband James, the second Marquis of Douglas due to false accusations of infidelity.

Often the development of oral folk tradition tends towards simplification and generalisation; the wearing-down process gradually erasing the history of long complex narrative story ballads in favour of shorter, more widely relatable sentiments. However, in this case it seems the opposite has occurred, as the more popular “Waly Waly” song may be the earlier strand, and the “Jamie Douglas” ballad the result of an enterprising balladeer using a few of the verses of the love song of the anonymous rejected woman as the framework on which to build his historical storytelling.

This is one of those ballads that has developed into two distinct strands, and while some scholars might insist they have their own histories and should be kept as distinct entities, in the Roud Index they are combined, so this is how they are presented here.

Music

Due to the widespread appeal of the “Waly Waly” love song, and its crossover to more classical and popular realms, the playlist is long, but not entirely folky. The most prevalent classical version is the 1946 arrangement by Benjamin Britten. Britten took an Irish melody from the Waly Waly spinoff “The Water is Wide”.

Many popular American singers have covered this. Here, for example is James Taylor.

In terms of more traditional folk versions, we should start with one of the earliest official recordings I could find, from the 1961 album “Two Way Trip” is Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger’s beautiful unaccompanied duet. This uses the tune from the William Thomson collected version from 1726 (see sources below) - the most common tune used in modern traditional versions.

I’m a big fan of Buffy Sainte-Marie who always tackles traditional material with great passion and imagination. Her version of Waly Waly is no exception, her distinctive voice accompanied by her own playing of the mouthbow.

A striking modern version in a similar vein can be found over on Bandcamp from Minnesotan singer Ellie Bryan.

In terms of versions that draw from the Jamie Douglas narrative, they are rare, but mostly stem from the June Tabor version from her 1976 debut album “Airs and Graces”.

A superb modern version can be found from Martin Simpson, whose plaintive slide guitar fits the song perfectly.

Another modern version, from Kate Burke and Ruth Hazleton, also has some beautiful instrumentation.

Finally, I enjoyed the amateur lo-fi modernist indie garage-recorded stylings of this one, all the way from Ontario collective Loon Base.

Not in the playlist as it is part of a much longer file is this version from County Wexford in Ireland. The County Wexford Traditional Singers Archive features 876 tracks recorded by John O’Byrne and Phil Berry from The County Wexford Traditional Singers from January 1991 to February 1996. This version under the title “The Water is Wide” was sung someone we only know by “P. Parker” - presumably not Spiderman.

Rare finds

Mary Humphries and Anahata are a folk duo currently residing in West Yorkshire. Their CD “Floating Verses” is now out of print, but I tracked down a copy - here is a clip of their version of Waly Waly. This is the variation that doesn’t mention the overly credulous Earl Douglas.

The sleevenotes, via Mainly Norfolk, are thus:

Collected by Cecil Sharp from the delightfully named Mrs Elizabeth Mogg aged 74 of Holford, Somerset, on 30 August 1904 [VWML CJS2/9/504] . Mrs Mogg, according to Sharp, consumed prodigious amounts of snuff. It must have helped her voice to stay clear as the tune has a very large range for a folksong—just three tones less than two octaves—bottom F to top C in this recording. The song is entirely composed of floating verses from a variety of sources and has no actual story-line.

Sources

Here are the Roud Index entries - it’s worth also clicking the “Audio” option to hear find some wonderful source recordings of the more popular “Waly Waly” versions, for example Edith Ballinger Price from Newport, Rhode Island, who appears on a cassette of source recordings from collector Helen Hartness Flanders, from around 1945. Here is a clip.

It’s a little tricky to find the song on the Archive.org link above, so for my beloved premium subscribers, the full song can be found after the paywall.

Francis Child’s notes. Unsurprisingly, Child focuses on the narrative Jamie Douglas ballad versions, although Ramsay’s “Waly Waly, gin love be bony” (see below) does get a mention at the end.

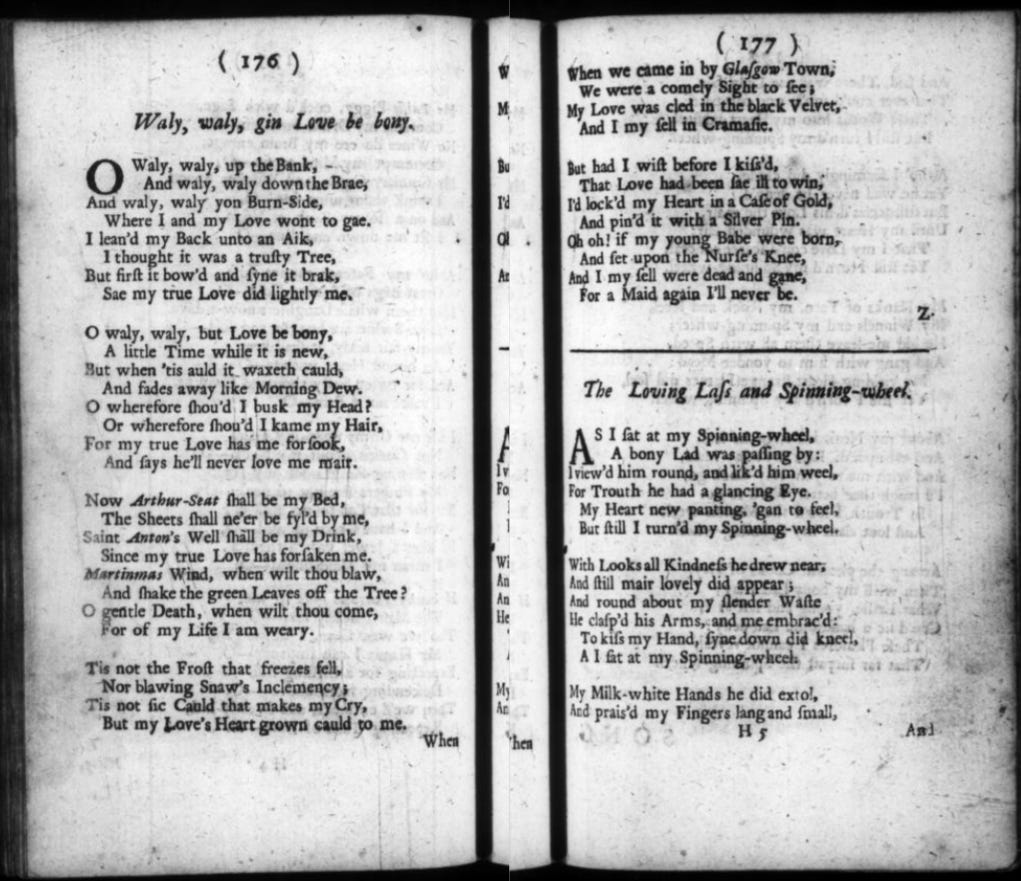

Notable Scottish literary powerhouse Allan Ramsay was the first to mention this ballad in his “Tea Table Miscellany”, an invaluable archive of songs and tunes published between 1723 and 1727. (The same song was published one year later by William Thomson in his Orpheus Caledonicus with a tune that is commonly used today.)

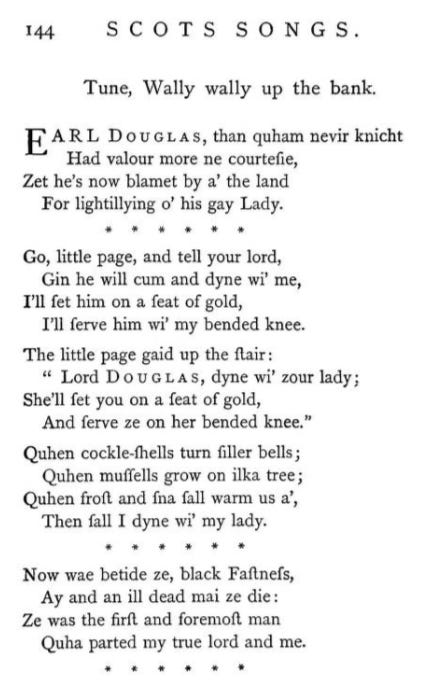

Fifty years later in 1776, five fragmentary verses were found of a clearly related ballad under the title “Earl Douglas” - the first to mention the high-born protagonists by name, and linking the story to true historical events. This was published by David Herd in his “Ancient and modern Scottish songs, heroic ballads, etc”, with the addition of the “cockleshells” stanza, which becomes a fixture in most subsequent versions.

More “Jamie Douglas” versions go on to be published (and often “improved”) by the prolific Victorian Scottish collectors Motherwell and Kinloch throughout the 19th century, while the generic “Waly Waly” seems to be the more popular and widespread song, especially outside Scotland.

In the US, the ballad in its “Waly Waly” form crossed over with Scottish and Irish immigrants in the 18th and 19th centuries, and was widely collected around the country, especially in Appalachia by Cecil Sharp in the early 20th century, and its popularity continued there with many recordings in the modern area, such as this powerful version from the wonderful Almeida Riddle.

Draft pages, audio guide, and a couple of full tracks

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.