ROUD 79: Mary Hamilton

AKA: Mary Hamilton, The Four Marys, The Queen's Marie, The Purple Dress, Mary Mild, The Duke o' York's Dother

Once again, this sad ballad is rooted somewhere between truth and fiction. When Mary Queen of Scots was sent to France in 1548, she had four ladies in waiting named Mary. However, none of them were called Hamilton, nor were executed for infanticide. This element of the story seems to come from elsewhere, but has been subsumed into the story in a way that is very common with these kind of quasi-historical ballads. There are records of a French woman in Queen’s service who was hanged for infanticide around this time, so it’s possible this story was incorporated into the ballad and her renamed to an honorary Mary for poetic reasons.

The Russian Mary Hamilton

Another popular candidate for the source of the infanticide-and-execution storyline comes from Russia, where there was another Mary Hamilton (a descendant of a Scottish family who had emigrated to Russia during the reign of Ivan the Terrible) who was a lady in waiting for Empress Catherine I of Russia. Hamilton gave birth to an illegitimate baby (probably the child of Peter the Great), subsequently drowning the child. Her crime was discovered and she was executed by decapitation, while dressed in white, on 14 March 1719.

Music

If you search for this song in your streaming music service of choice, approximately half will be Joan Baez, in various live and recorded versions. A good example is this, recorded in 1965 at the BBC, and thankfully not lost or destroyed in the meantime.

Thanks to the deserved popularity of Baez, and the simple plaintive tune, this is the prevalent version of the song that is played today. And not just in English, here is a version translated into French:

However, 20th century tune collector Bertrand Bronson collected a dozen melodies for this ballad, and it is interesting to pick out from the playlist a couple of those that differ from the norm.

My favourite tune is this, originally found by early 20th century Scots collectors Gavin Greig and Alexander Keith. (Bronson correctly points out the similarity to popular festive song The Holly and the Ivy in the second half.) The collected tune was sung in 1900 by William Wallace (not that one, unless time travel was involved), the version passed down from his mother some 70 years before, and has been memorably repeated a few times, such as this haunting unaccompanied version from Ellen Mitchell in 2001.

Compare this to the very recent and as ever delicately beautiful recording made by Alasdair Roberts:

It’s always interesting to hear something from the Harris Manuscript. Thankfully Katherine Campbell has recorded this interesting version in 2004, accompanied on solo fiddle.

Finally, as I write this on an always welcome Bandcamp Friday, here are a selection I found on that site.

Sources

Unsurprisingly, for a popular song with many recorded versions, there is plenty of coverage of this ballad in all the usual places, and some less usual ones. Following are a few highlights.

Francis Child’s introduction to his 29 versions of this ballad is a lengthy one. He spends some time trying to establish a single narrative that unites all the versions, and fails. And then outlines the two main contenders for the true historical Mary Hamilton, but draws no final conclusion.

For a more strongly opinionated view, it’s worth reading the commentary from handsomely mustachioed 19th century Scottish ballad scholar Andrew Lang. He is furiously adamant that there is no balladic connection to the Russian Mary Hamilton.

The book “Weep not for me : women, ballads, and infanticide in early modern Scotland” by Deborah A. Symonds (1997) contains a comprehensive analysis of the ballad, and is well worth reading for a great overview.

William Motherwell’s commentary is always worth reading as he is usually open to his own sources, giving us a through line from the publication of his 1846 “Minstrelsy Ancient and Modern” back through the known variants at the time. In this instance it doesn’t give us much more insight than Child, but does give a useful account of the French woman from Queen Mary’s court who was hanged for having an affair with the queen’s apothecary.

The ballad has been found, rarely and usually in fragments, in the US. A couple of useful accounts of this; first from “The Ballad Book” by John Jacob Niles, where he recounts the tale of his father teaching him the only complete version of the ballad to be found in America. (A claim to be taken with a pinch of salt, as rumours abound of Niles’ less than honest collection practices.) You can hear Niles singing his version in the playlist - here it is:

The second and more comprehensive account of the ballad’s existence in the US is to be found in “More Traditional Ballads of Virginia” by Arthur Kyle Davis.

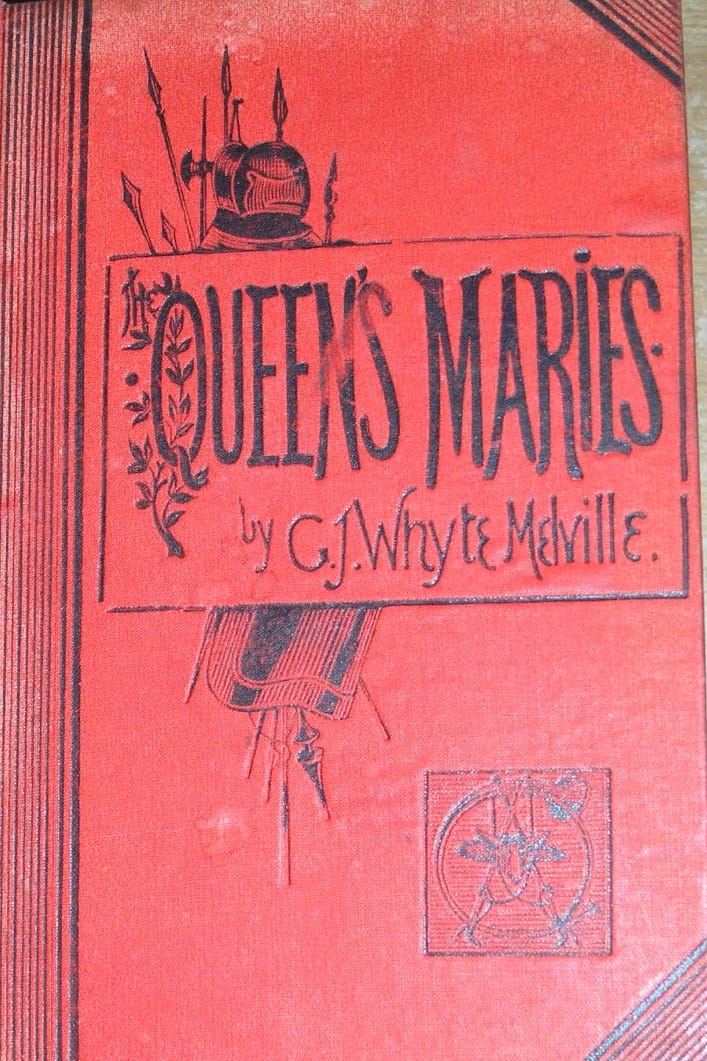

Finally, if you are intrigued enough to want to read some fiction based on the four Marys of Mary’s court, this 1862 historical romance novel should have all you need.

You can read the whole thing here.

(It was clearly a topic close to Melville’s heart, as in 1869 he also published this poem inspired by the story.)

Draft pages and audio guide

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.