When Child was compiling his collection of ballads, he found a version of this, but deemed it unworthy of its own entry, considering it a crude copy of The Death of Queen Jane. There were a few similar lines, but due to the wildly differing storyline Child’s argument for plagiary seems weak, and the ballad has certainly developed a life of its own in the modern recorded era. It’s stark and gruesome imagery of the drowned Duke and his ensuing disembowelment has made for some spellbinding interpretations.

Plagiary or not, the evolution of this ballad seems to start in a primordial soup of songs about dead (normally drowned) Dukes, with various potential early versions lamenting the death of The Duke of Grafton (or sometimes Grantham), while history tells us that the real Duke of Grafton died in battle, not by drowning. However the Duke of Suffolk did in 1450 meet a similar end to the one given in the song, and collector Lucy Broadwood speculated this could have been the real source of the story, with names changing throughout time in the usual ad hoc way.

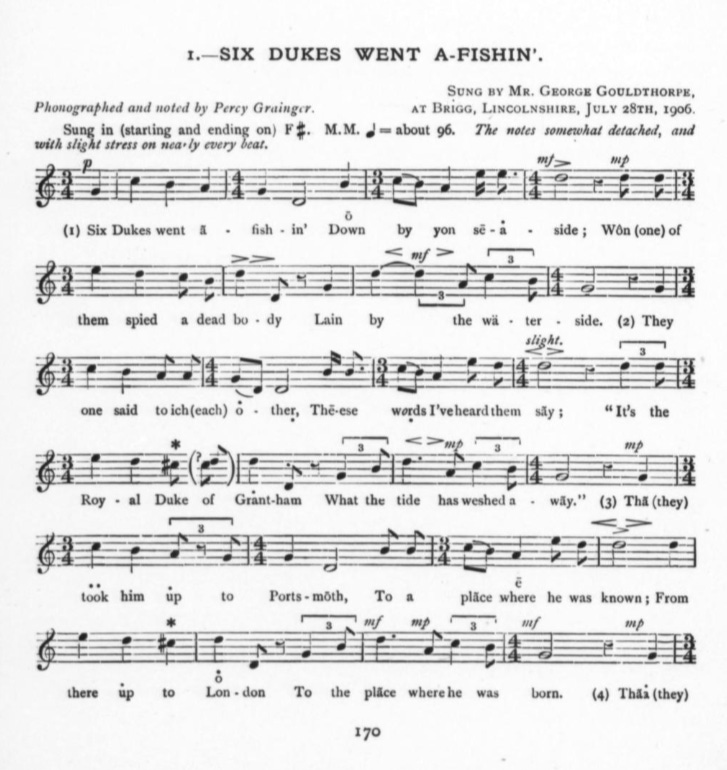

Music

For a ballad that started life as a footnote, the Youtube playlist is a surprisingly long and varied one, starting from one of the earliest sets of audio recordings we have, those scratchy time capsules made by Percy Grainger in the very early 20th century. Here is Lincolnshire lime-burner and occasional workhouse inmate George Gouldthorpe singing for Grainger in 1906.

At the other end of the spectrum is this epic prog folk interpretation from seven piece band Mishaped Pearls.

I also love this from Lisa Knapp, a familiar tune but as ever with Lisa she develops it interestingly into something that is by turns delicate, light, dark and visceral; the perfect blend for the song’s sad but gruesome content. This is from her stunning 2007 debut LP “Wild and Undaunted”.

Finally, this from the great Andy Turner’s impressive Folk Song a Week project is well worth a read, and a listen.

Sources

The earliest known source for this ballad is a 1690 broadside, from whence the image at the top of this page came.

It recounts the supposed death of the first Duke of Grafton, Henry FitzRoy (illegitimate son of Charles II) who died in 1690 in battle in Ireland. While the Duke was not found drowned as in the ballad, it is recorded that he had his internal organs removed before transport back to the UK in order to preserve the body, echoing the gruesome disembowelment recounted in the song.

Francis Child found this ballad mentioned in Longman’s Magazine in 1890. Here is the relevant entry, with an interesting note on the persistent tradition of burying entrails before transporting the body.

Interestingly, Child made no mention of the broadside ballad of 1690, although given Child’s well known antipathy to broadsides, it’s not surprising.

One of the key source recordings is the very scratchy phonograph of George Gouldthorpe, which you can hear in the music section above. This was expertly transcribed for posterity in the esteemed Journal of the Folk Song society in 1908:

In Cecil Sharp’s “100 English Folk Songs” he records a version from an 80 year old William Atkinson, a Sheffield silversmith who had ended up in a workhouse in Marylebone London after a bout of illness rendered him unable to work. The notes contain a number of interesting points, including a summation of Lucy Broadwood’s musings on the identity of the drowned duke.

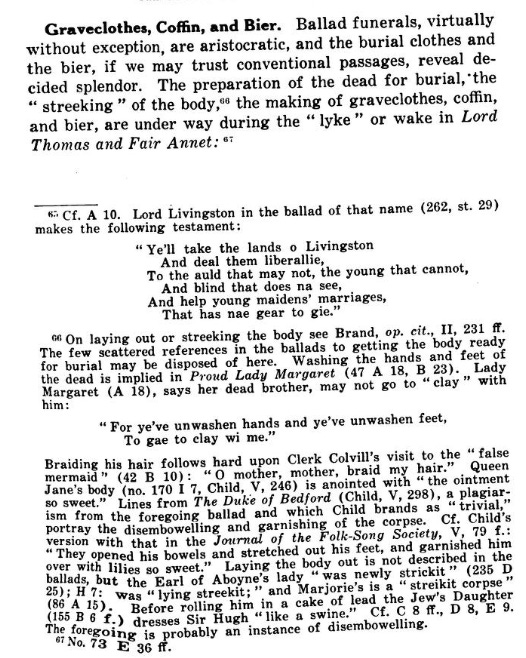

The 1927 thesis on “Death and Burial Lore in the English and Scottish Popular Ballads” by Lowry Charles Wimberly is always interesting, and has a couple of good footnotes regarding the extensive death and burial imagery in this song. Firstly an historical context for the ritual dismboweling of the Duke’s body:

and secondly, the note that the “flamboys” that appears in many versions is a corruption of “flower my boys”.

Draft pages and audio guide

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.