Preamble: Unfortunately, like many who work in the realm of traditional song, sometimes I have to spend time working in more lucrative but mundane pursuits in order to make enough money to survive. The last few months have been one of those periods, so apologies that this latest installment has taken so long to arrive. As well as hopefully speeding up my output, there will also be more free gifts coming soon, which I hope will be enough to ensure your continued patronage, for which I am endlessly grateful.

I’m starting to develop a taxonomy of the historical veracity of traditional songs. I’d suggest there were four broad categories:

a) Completely fictional ballads

b) Ballads where the characters are real historical figures, but the events are partly or entirely fictional

c) Ballads based on true events, but the characters are either fictionalised, or lost to history

d) True stories in ballad form

This ballad fits neatly into category (b). Queen Eleanor of Aquitane did indeed marry Henry II in 1154. But she was recently divorced from King Louis VII of France, with whom she had two daughters, making the central confession of the ballad - the fact that she had lost her virginity to Earl Marshall rather than Henry - an impossibility. So rather than recounting an actual confession, it seems the ballad took a popular story (possibly derived from a medieval French fabliau - see below) and applied it to these historical figures; a common way for balladeers to give the story some narrative spice. A bit like how some licentious gossip about Taylor Swift and Jack Nicholson would be immediately more commercially valuable than the story about your Auntie Mabel and the man that worked in the dry cleaners.

There is also a prevalent theory that the narrative, which paints Eleanor in such a poor light, is the work of the Catholic church, with whom she was not popular at the time.

Absolutely Fabliaux

Fabliaux were narrative poems written by French minstrels (or jongleurs) between about 1150 and 1400. Their subject matter tended to be of the more comic and scurrilous kind, often including tales of infidelity, scatological obscenity and other topics considered taboo by the church and other institutions of the day.

While their origins were confined to a relatively small area of Northwest France, their influence travelled widely, and can be found, for example, in medieval poetry, such as the epic poem (familiar to those of us with an interest in traditional song) Reynard the Fox - a tale that travelled from France all over Europe, at each stop taking on the customs and lore of wherever it was found. Other literature influenced by fabliaux includes Giovanni Boccaccio's “Decamerone” and Geoffrey Chaucer's “Canterbury Tales”. The specific fabliau that seemingly has influenced Queen Eleanor’s Confession seems to be “Le Chevalier qui fist sa fame confesse” or “The Knight who confesses his fame”. See more in the Sources section below.

Music

A nice selection here in the Youtube playlist. Most are jaunty versions of the only surviving original tune as published in Bertrand Bronson’s “The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads”. Here is a prime example from the Chad Mitchell Trio from 1964:

(If you were in any doubt as to the possible longevity of a career in folk music, take note of the fact that these chaps gave their last performance in 2014, after 55 years in folk music together.)

Ewan MacColl’s version takes a darker tone, using a tune of unknon origin.

According to the sleeve notes, this song was beloved by Ewan and Peggy’s daughter Kitty, who, at aged nine, would lustily sing along on family car journeys. It wouldn’t seem an obvious choice for a family singalong, but you can’t doubt the veracity of the story, as it’s Kitty’s strong and confident voice you can hear on the above recording.

Finally from the playlist, this nice version from The Exiles to their original (though containing echoes of the MacColl tune above) 1967 tune is becoming something of a standard, as a version of it was recorded by the brilliant Furrow Collective in 2016.

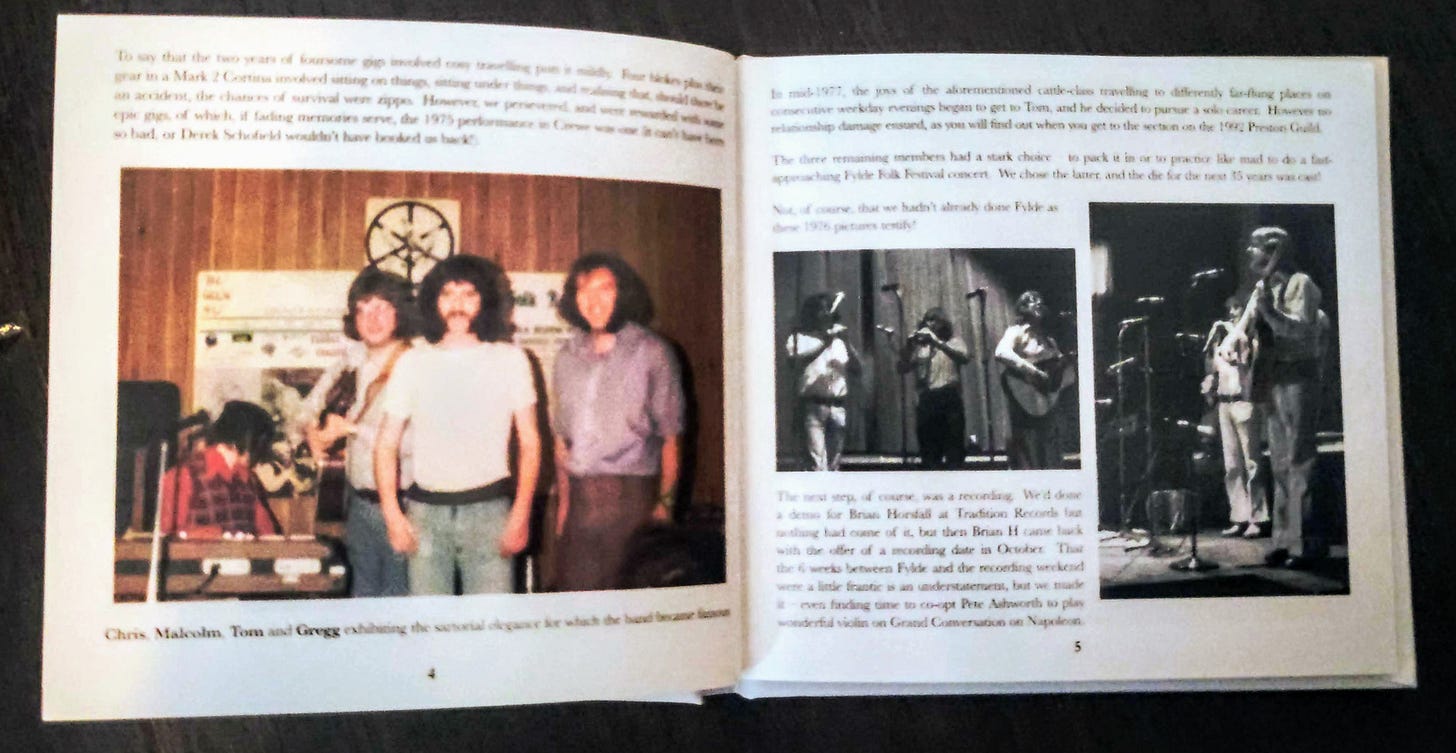

Outside of the sanitised domain of online music publishing, I found an interesting postal-order-only artefact in the form of a book and music package from long running Lancashire folk band Strawhead. Not only does it contain a version of Queen Eleanor’s Confession, a clip of which can be found below, but the book is a fascinating account of the life of a working (or attempting to work) folk band starting in the mid 1970s, written with humour and a refreshing lack of cynicism. Oh, and some wonderful photos.

I can heartily recommend it, for all of the aforementioned reasons, plus you get 300 songs complete with sleeve notes, lyrics and sometimes music notation. Here is a clip of their version of Queen Eleanor’s Confession, from their 2002 album “A Hertfordshire Garland”*.

*How a group of Lancastrians ended up making a Hertfordshire folk concept album can be read about in their book, as you might imagine.

Sources

There is unusual accord in the historical asessment of this ballad. This short introduction from Alexander Whitelaw’s “The Book of Scottish Ballads” provides a good summary, with the additional supposition that Eleanor’s moral crimes against Henry might have been rewritten versions of crimes she may have committed against her previous husband, Louis VII of France. Although the more likely and more prevalent theory that the story was confected by a disapproving Catholic balladeer some time later seems more likely.

Further to the discussion of French fabliaux above, this is a good article from 1908 with particular focus on the parallels with the ballad of Queen Eleanor’s Confession.

You can read the full article here.

For some scholarship from later in the 20th century, this ballad is tackled by US folk collector Helen Hartness Flanders in her excellent 1963 volume “Ancient Ballads”.

Draft Pages and Audio Guide

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.