ROUD 73: Hugh of Lincoln

Sir Hugh or the Jew’s Daughter, Little Sir Hugh, The Jew’s Garden, The Queen's Garden, It Rained a Mist, Fatal Flower Garden, Little Sir William

Preface

It’s an unfortunate time to be writing this, as we watch untold horrors unfold in Israel and Palestine, since this ballad primarily concerns some anti-Semitic fearmongering that echoes painfully down the ages all the way from the 13th Century. However, if we are to be honest about traditional music, and about history generally, is that all too often it is a macabre museum of bad ideas and self-defeating cruelty, and if we were any more sensible as a species, we would evolve beyond it all. Anyway, don’t read it right now, if you’re not feeling up to that sort of thing. Peace to everyone.

On 12th August 1255, a little boy called Hugh died in Lincoln, aged nine years old. His body was found in a well, and theories of the cause of death immediately started to circulate. At the time, Lincoln was home to a large Jewish population, and Christian officials sought to blame them (without any evidence), seemingly in an effort to sow division and unrest, and thereby increase donations to the church.

It all sounds depressingly familiar.

Anyway, this song documents this supposed crime. The early versions are all quite clearly anti-Semitic, although later the song evolves to implicate other minorities, including the oft-persecuted traveller community, but also, especially in America, sometimes a wealthy figure is named the culprit, in the form of a Duke or a Queen, or the catch-all term for a high status woman, “a lady gay”.

Music

Despite (or sadly because of) its inflammatory subject matter, the song flourished in popularity from its first documented appearance in the 17th century (although its prevalance at that time would indicate it had been circulating for a very long time before that). By the end of the 19th century, Francis Child found 21 versions not just from England but also from Ireland, Scotland, Nova Scotia and all round the US mainland.

This is reflected in the quite large and varied Youtube playlist. It contains some interesting field recordings, such as this Hamish Henderson recording of Maggie Stewart in 1954.

Fast-forwarding to the revival era, here’s a characteristically Steeleye-Span-ish live version from Steeleye Span in 1975. An example of a version that eschews the need to cast aspersions on an entire race of people. I’m sure they thought, as I do today, there is plenty of interest in the story without that particular element.

An example of the US tradition would be the “It Rained a Mist” variation. Somehow it entered the nursery rhyme oeuvre, which might seem odd (but not unprecedented) for such a tragic tale. Interestingly all mention of children dying in wells is removed in this version to leave a simple, innocent lullaby about children playing outside:

(I’m unable to miss an opportunity to mention Cath and Phil Tyler when any song from their incredible 2018 album appears, and this is no exception - clearly a version of the lullaby above, but with the some of the more macabre elements included.)

Haunting early US recordings of this song can be found at the recently published and immediately indispensible online archive of Alan Lomax field recordings. For example here’s school child Sally Belle Turner of Greasy Creek, Big Laurel in rural Kentucky, singing it to us all the way from 1937.

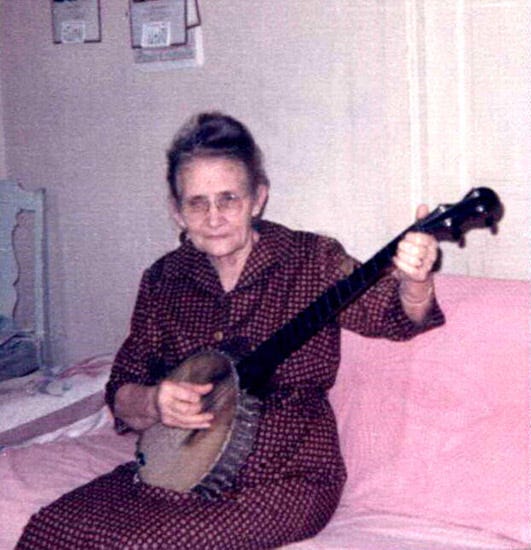

Another example from the same archive is the from the Ozark folk-singer Ollie Gilbert, who apparently knew over 300 songs. Here she is recorded in 1959.

The song continues into the 21st century, with well known contemporary folk singers such as Alasdair Roberts and Sam Lee keeping the song alive. Ireland also has something to say on the matter. Here is Irish singer songwriter, and erstwhile vanguard of the 1980s Dublin punk movement, Gavin Friday, clearly working from the US lullaby template:

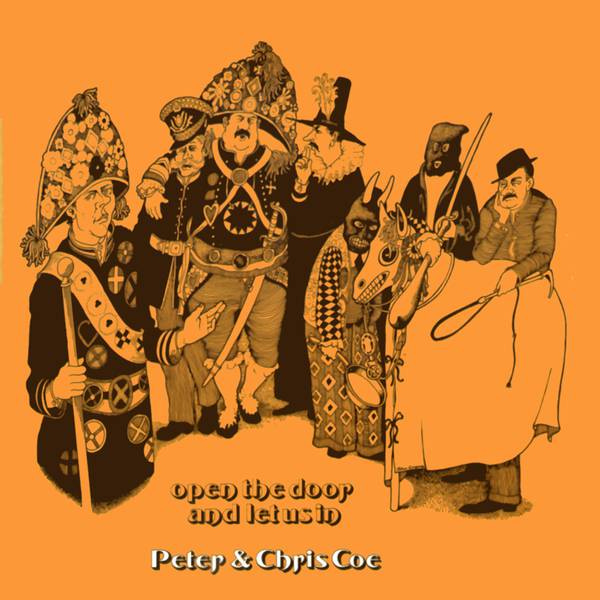

Finally, outside the dingy confines of the internet, and into the wide world of circular plastic music. Some time ago I bought this 1972 classic:

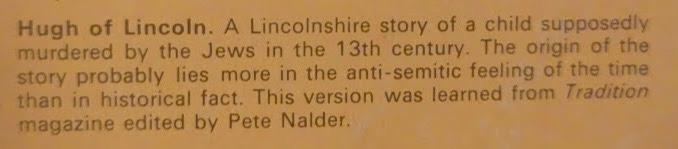

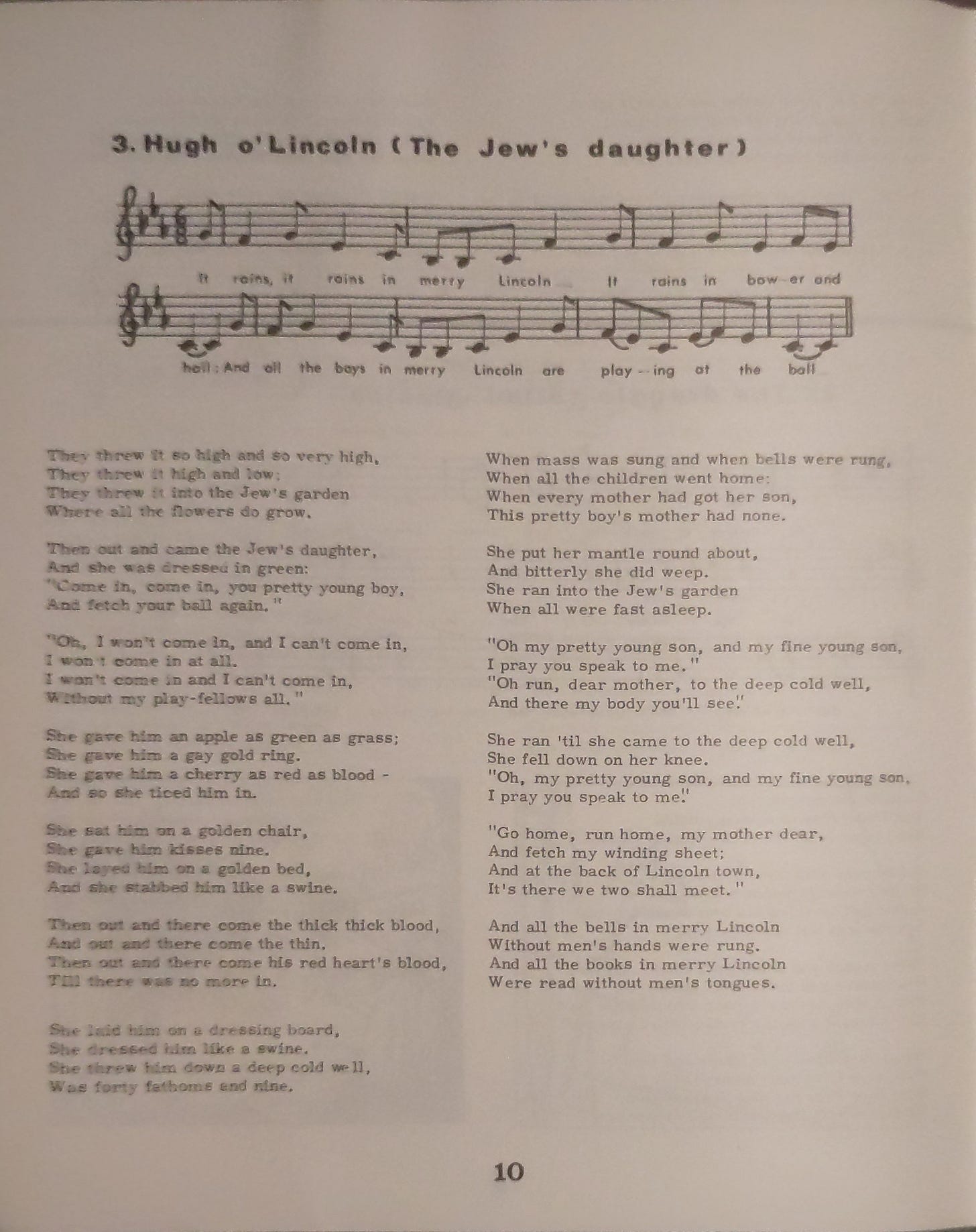

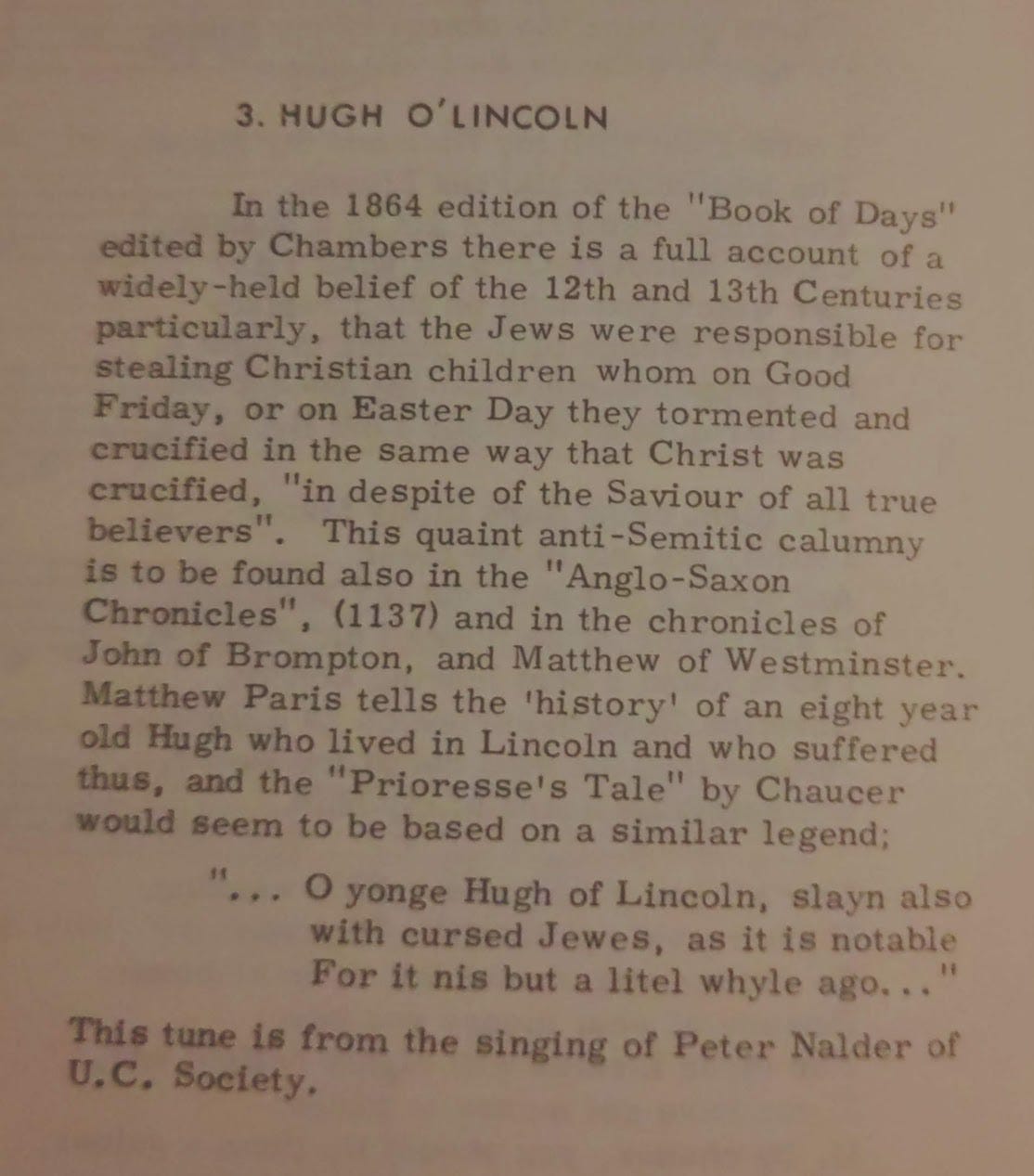

It features what is probably, due to its limited availability, a little heard version of Hugh of Lincoln. Here are the sleeve notes:

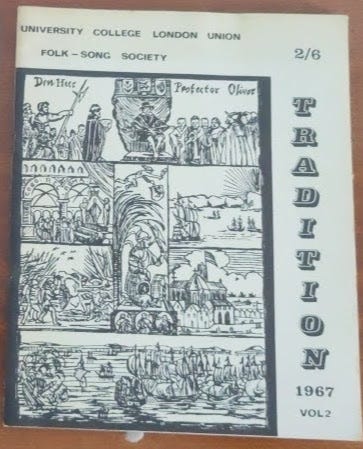

I managed to track down a copy of the 1967 issue of “Tradition” magazine mentioned here. It was the magazine of the University College London’s folk music society. It might sound like a modest little periodical, but it included extensive articles from folk heavyweights such as Ewan MacColl, Martin Carthy, Stan Hugill and A. L. Lloyd.

And here’s a clip of the Coes’ performance of it. (As usual, I’ll put the full track after the paywall.)

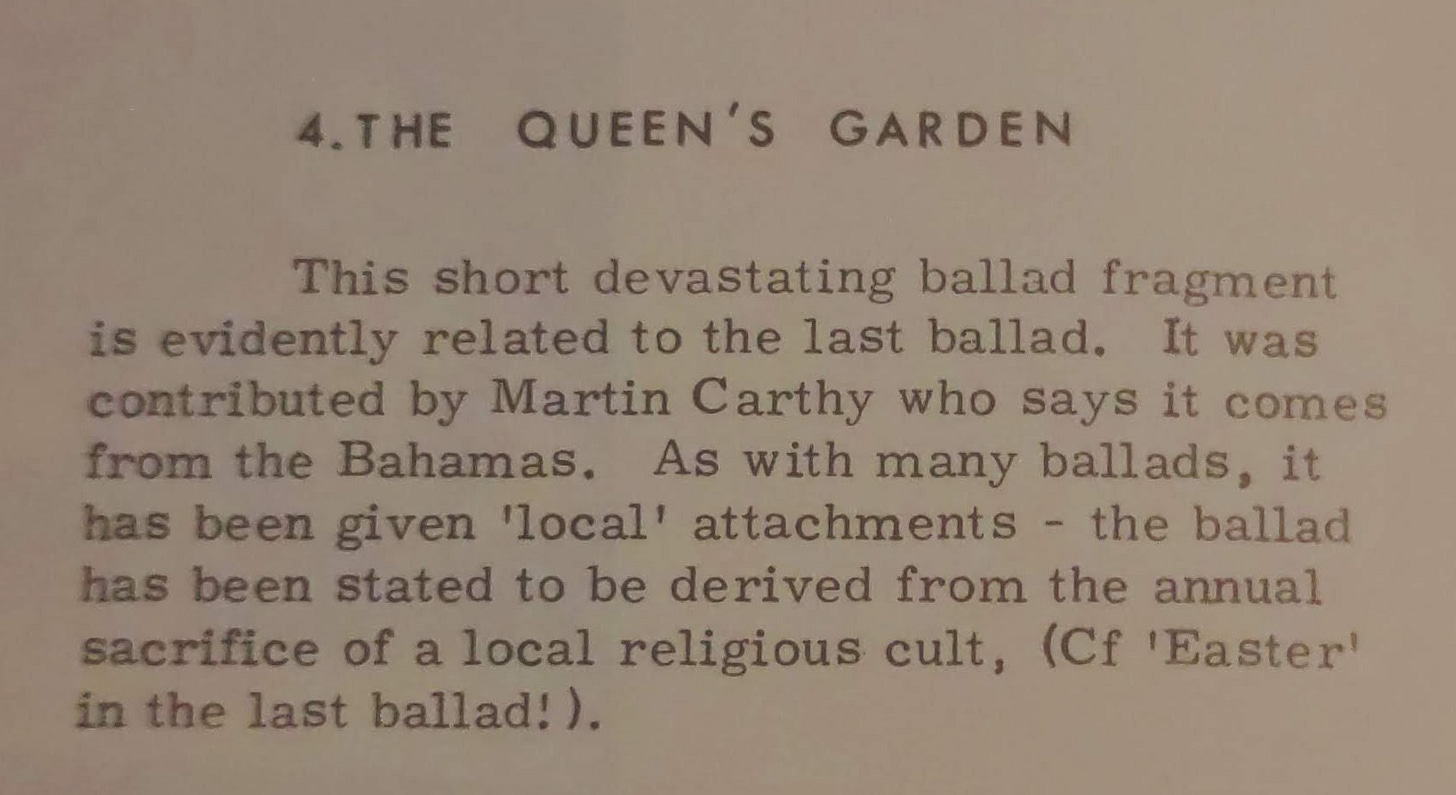

As a side note the next song in the magazine is another version of this ballad, one of the simpler Transatlantic versions, under the title The Queen’s Garden:

Apparently this hails from the Bahamas, according to Martin Carthy.

Sources

The 1881 text from which the images were taken at the top of this article is George Barnett Smith’s “Illustrated British Ballads, Old and New” - he includes this somewhat encouraging short introduction where he dismisses the antisemitic sentiments as “unjust”.

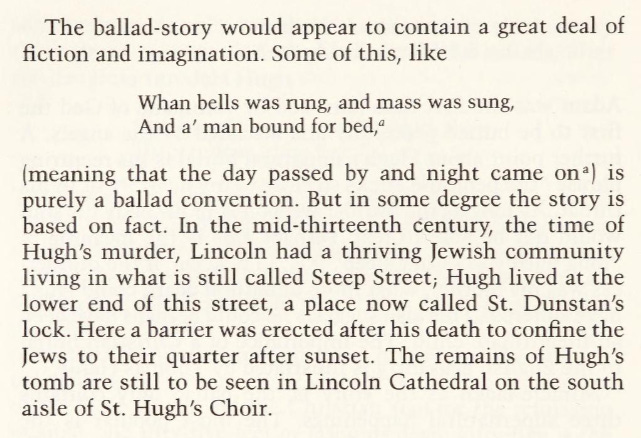

An in-depth analysis of the ballad, including its folklore and role in historic anti-semitism can be found in the 1991 anthology of articles “The Blood libel legend : a casebook in anti-Semitic folklore”. Brian Bebbington is comprehensive in his review, identifying the ballad as being packed with Christian imagery, which would certainly be explained by the theory that the story is largely a confection of the Protestant church intended to promote its own beliefs over any other. Bebbington ends with the stark piece of historical information that the real Hugh did indeed live down the road from the Jewish community in Lincoln, and how they subsequently had a curfew placed upon them after the accusations were made.

There are plenty more articles and books around the legend of Little Sir Hugh and his unfortunate role as an origin story of British anti-Semitism. For example, this Jstor article (requires free registration to read the whole article) examines the prejudices of Chaucer, who included the legend in his play “The Prioress’s Tale”.

By the usual inexplicably arcane mechanic, the song became very popular in the US, and somehow evolved into a popular children’s nursery rhyme and lullaby. This is documented in the 1903 book “Games and songs of American children” by William Wells Newell, who was an American folklorist who founded the American Folklore Society and wrote a number of books on the subject. He found a fascinating, precious and surprisingle complete version of Hugh of Lincoln, albeit under a slightly but significantly different title, sung by a young girl of Irish parentage who lived in a run-down workers community on the edge of Central Park, which was at the time acting as a busy quarry mining stone to build the now highly desirable “brownstone“ housing found in East Manhattan. The fact that this Irish labouring community had taken the ballad and removed any anti-Semitic content, instead opting for the high class “duke” as the evil-doer, shows the ballad gravitiating towards the source of the natural grievances of its singer. Following is Newell’s introduction, but, [trigger warning] as it was written in 1903, does contain some outdated terms, although if you can bear it, it is still well worth reading for the poetic description of the industrial hellscape in which this old English Ballad was found to be residing.

Draft pages and audio guide

Plus the bonus full track “Hugh of Lincoln” by Pete and Chris Coe from 1972.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.