ROUD 64: Willie O' Winsbury

AKA: Tom the Barber, The Rich Shipowner's Daughter, There Was a Lady Lived in the West, John Barbour, Lord Thomas of Winesberry and the King's Daughter, William of Barbary, William of Winesbury

Administrative preamble: Sorry there has been a bit of a gap with this one. I have had some technical problems with Substack which have taken a little while to iron out, plus life has been getting in the way, but in a good way for a change. Hope you enjoy this one!

This ballad that tells the story of a handsome rover returning from his travels to claim his lover has become synonymous with Andy Irvine’s version since the 1960s. Today we can find many interpretations of Irvine’s famously accidental arrangement, but also a far more diverse range of source recordings and collected versions.

It is possibly most notable due to the striking admission of the King, that Willie is so handsome that if his daughter did not marry him, the King would marry Willie himself. This fascinating aspect of the ballad is discussed at great length in the podcasts mentioned below - I commend them to you.

Music

There is *plenty* to listen to for this one. As mentioned above, most modern interpretations follow the Sweeney’s Men template, which, thanks to Andy Irvine’s recklessly lackadaisical use of Bronson’s famous collection of tunes for Child Ballads, is based on a tune originally collected for Roud 57 - False Foodrage. However, there are a wide range of other interested stuff hidden in the usual Youtube playlist, including some lovely source recordings.

Over on Bandcamp I also found a plethora of versions not available elsewhere - For example, I enjoyed this ethereal Belgian version:

Another interesting by-product of this ballad is its use as an instrumental. The irony of an instrumental piece based on a tune for one ballad being given the title of another (and further, in Andy Irvine’s famous tale, he initially thought he had mistaken it for the tune of a third ballad - Willie O’ Douglas Dale) is not lost on me. Still, here are a couple of lovely versions, first for that possibly underused instrument in instrumental folk music, the double bass:

and second, the great prog-folk troubadour Henry Parker’s superbly mellifluous guitar stylings:

Outside of the tangled greenwood that is the internet, many versions are locked away on discs of plastic scattered across the globe in people’s dusty attics. I have collected a few to share with you. The 40 year old machine I currently use to play them is being a bit temperamental - I think it might need a Fonz-style thump on the side - so apologies for the questionable sound quality. Personally I think it all adds to the vintage aesthetic. These are just clips below, full tracks can be found after the paywall break. Seems like a good time for an advert.

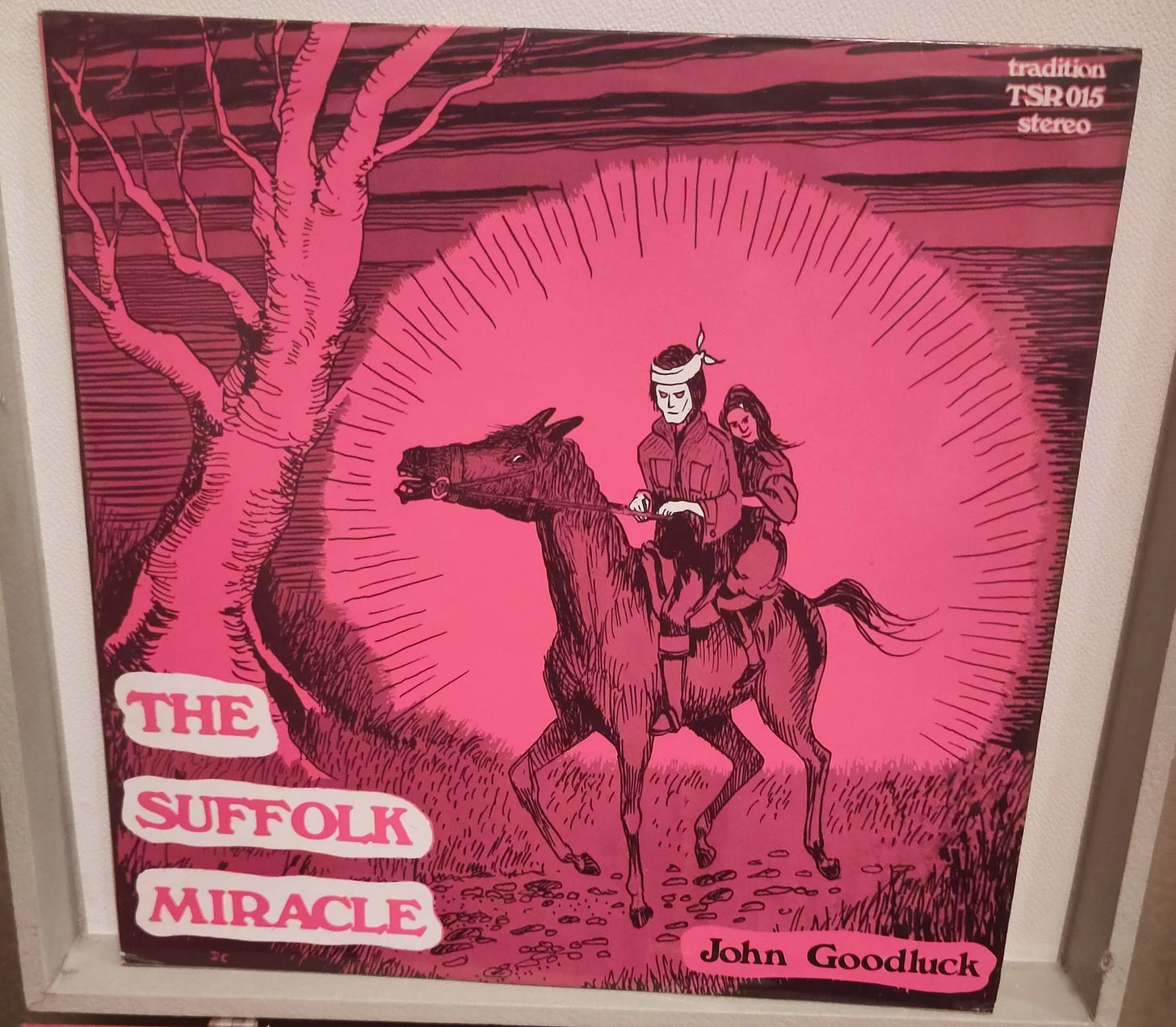

First up is the album with surely one of the most captivating covers in the entire folk catalogue. Just an incredible illustration by David Crossland (I can’t find any more info on Crossland, unfortunately; I would love to see his other work - if you have any info, please let me know). This album is pretty hard to find under £50 but just about managed not to break my rule of not spending more than I would on a new CD for this slightly battered one. The song was apparently one of the most beloved of the brewer-turned-folkie.

Clip from “Willie O'Winesbury” by John Goodluck:

Next up is Steve Turner. Lots of interesting takes on his 1984 album Eclogue, well worth picking up as it normally goes (as is the case for a lot of late 20th century folk vinyl) for charity-shop prices. Despite the sparsity of the solo concertina accompaniment, it feels satisfyingly rich.

Tony Rose inevitably had a go at it on his relatively late-period 1984 album Poor Fellows. His version was collected by Cecil Sharp from Mr Gordge of Bridgewater, and goes under the title of “Tom the Barber”.

Finally there is Brian Peters, whose version (titled “John Barbour” on his 1989 album Fools of Fortune) is based on one of the Newfoundland versions collected from Charlotte Decker in 1959 and published in Kenneth Peacock’s huge 1965 collection of songs from that area.

I did buy a couple of CDs for this song as well. Probably my favourite is this from Ken Wilson and Ian MacFarland from their 2017 unaccompanied traditional song. It is another of the “Tom the Barber” variety, and again comes from the aforementioned Mr Gordge of Bridgewater.

The same version was recorded around the same time by one of the finest of the new generation of folk voices, Cohen Braithwaite-Kilcoyne, on his Outway Songster album. Compare and contrast.

Podcasts

For this entry in our Roud-the-world trip, we have the benefit of some excellent podcasts, which not only share even more interesting recorded versions, but also have some excellent research behind them. Possibly foremost in the latter category would be Jennie Shaw’s always excellent Handed Down podcast.

One of my favourite folk podcasts of all time (which seems to be “resting” at the moment, although possibly not forever) is the Old Tunes Fresh Takes podcast, which looks at a ballad and encourage musicians of all genres to record new and always wildly varying versions of the songs they feature. They somehow recruited beloved comedian and famed lover of esoteric music Stewart Lee to discuss and then listen to the versions of Willie O’Winsbury recorded especially for the show by its listeners. It’s a beautiful thing.

All of the delightfully diverse full versions of the “Fresh Takes” can be found here.

Finally in the podcast arena, there’s the magnificent Dublin-based Fire Draw Near traditional music podcast from Lankum’s Ian Lynch. Currently only available to his Patreon subscribers, it will be launched into the regular FDN podcast feed in due course.

Willie O’ Winsbury and sexuality in the ballad

Over the last ten years or so, the interest around this ballad has been largely centered around the King’s striking admission of bi-curiosity regarding Willie’s handsomeness. It’s striking mostly due to the lack of (or possibly removal of) almost any mention elsewhere of any kind of same-sex love or gender fluidity across the thousands of traditional ballads that we know today.

I found an article written in 1995 that is an overview of the sexual diversity that can be found in traditional ballads that includes discussion of Willie O’Winsbury. Trigger warning: Despite it containing some helpful information regarding this rare material, it does contain some outdated language. If you would still like to read it, it can be found here. https://www.jstor.org/stable/54137

If this topic is of interest to you, please refer to the lovely people at Queerfolk who are developing resources and events to hopefully give space to traditional song outside of its historically heteronormative confines, and make it more welcoming to the LGBTQIA+ community.

To be gay, or not to be gay?

Roud 64 gets a mention in the 2009 book ”So Long as Man can Breathe”, a treatise on Shakespeare’s sonnets, and the myriad speculations on the meaning and history behind them. The author Clinton Heylin documents the fervent attempts of historic scholars from less enlightened times to insist that Shakespeare did not have a non-heterosexual bone in his body, all based on a passing literary expression of male attractiveness in Sonnet 20. It’s fairly damning of some mostly erstwhile historians and their clearly rampant homophobia; you can read it here if you wish.

Sources

Pretty much all the scholarship you need is covered above in the Podcasts section, so there’s little need to repeat it all here, I would recommend popping those on while you are doing the washing up.

If it’s reading you are after, as usual with the Child ballads, the most comprehensive account of the ballad and its early collected versions come from Child himself. It is all neatly laid out in web form over at Bluegrass Messengers, god bless them.

Here’s our old friend Frank Sidgwick in his Popular Ballads of Olden Time, succinctly pouring cold water on one of the popular theories of this ballad’s potential real-life origins.

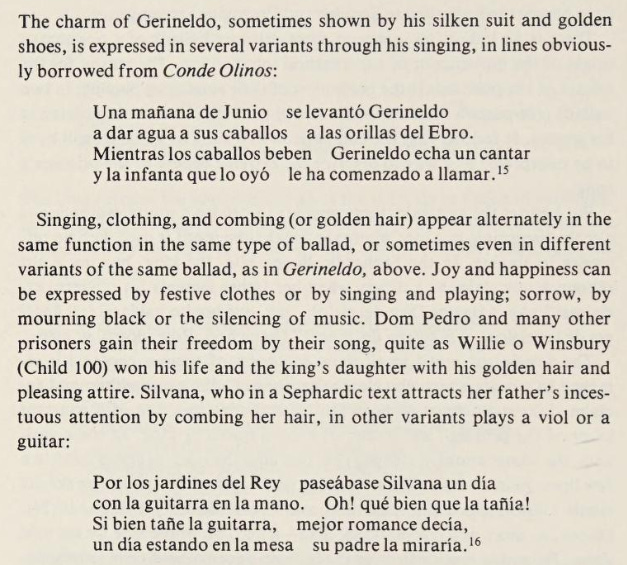

In the relatively niche field of golden flowing hair symbology research, Willie gets a mention in the interesting 1980 book “The perilous hunt : symbols in Hispanic and European balladry” by Edith Randam Rogers.

I found this interesting Ulster version in a 1979 book “Songs of the People: Selections from the Sam Henry Collection”.

This is the Robert Cinnamond version mentioned:

The above version is of the “Tom the Barber” variety, which is sometimes associated with North Africa and the notorious Berber pirates, for example by Tony Rose on the sleevenotes for his Poor Fellows album:

For some 200 years, dating from the mid-17th century, the Barbary coast of North Africa—present day Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria—was notorious pirate territory. ‘Barber’ seems to derive from ‘berber’, but whether this is the hero's nickname, disguise or genuine identity is uncertain. Other versions of Willie o' Winsbury have him “lately come from Spain.” In either case it must have seemed fairly exotic to Mr Gordge of Bridgwater from whom Cecil Sharp collected this fine tune.

A less exotic theory on the source of the name can be found in the Journal of Folk Songs from 1909.

A fine example of the “word ladder”-style games we can find ourselves engaging in if we have to much time on our hands. It’s all part of the rich tapestry of folk music. And at the end of the day, in folk as in life, people will ultimately choose the version of the truth that works best for them.

Draft Pages and audio guide, plus some bonus content

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.