ROUD 58: Jellon Grame

AKA: Jellon Graeme, Jellon Grame and Lillie Flower, Gil Ingram, Hind Henry, Lady Margerie, May-a-row, Jellon Graham

A rarely performed revenge ballad. This one has an ending highly reminiscent of the previous ballad, but with a much simpler, but more brutal setup. The murderer still gets his comeuppance though, this time at the hands of his own child.

Music

Again, not very much to listen to for this one. But also again, even though there’s not much of it, the quality is very high, and it’s all very interesting.

A mere six entries in the Youtube playlist.

I’m very partial to the Peggy Seeger version from her 1992 Folkways release “Songs of Love and Politics”. It’s the usual Seeger brilliance of taking a very simple melody and somehow keeping you riveted for 9+ minutes, but there is a tiny and curious bit of male vocal harmonising (from Ewan MacColl?) at about the 1.26min mark. It’s the kind of half-hearted joining-in someone might do if they were occupied with another complex mental task, like doing your accounts or working on a particularly testing jigsaw. See what you think.

No mention is made of the mystery harmoniser in the sleevenotes which simply say:

This is a very rare ballad. Since the publication of Child's English and Scottish Popular Ballads, it has been, to our knowledge, reported only twice in the oral tradition. This text, from the memory of M.A. Yarber, Mast, NC, is startlingly like the Child A-text. Child's other texts seem over-complicated in comparison. The simpler story remains a grand example of a genre not often found in balladry: that of patricide committed by a grown child.

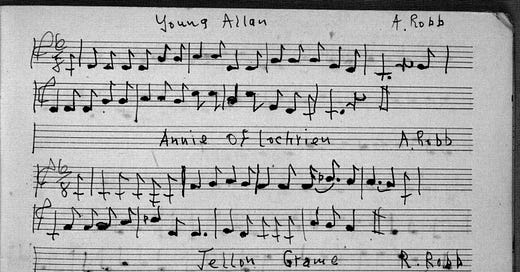

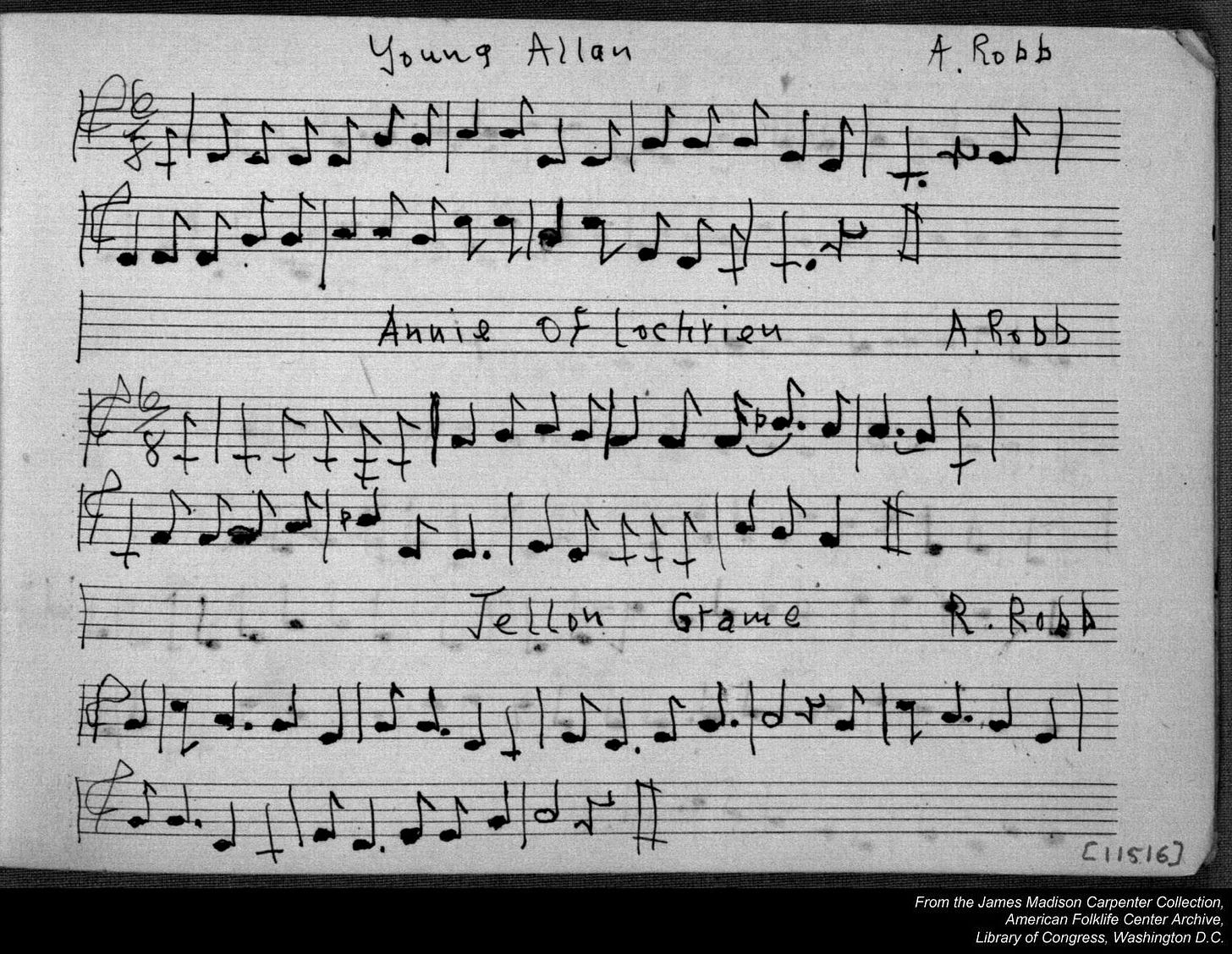

The only pre-revival source recording of the ballad comes from stone mason, farmhand and school janitor Alexander Robb of New Deer, Aberdeenshire, recorded on wax cylinders in around 1919 by James Madison Carpenter. It is scratchy by modern standards, but on the scale of wax cylinder recordings, it’s a pretty good one, if only a few verses, and half a tune:

This next one is from “Philadelphia's leading and longest-lived electric folk band” Broadside Electric - a humble but probably accurate boast - but I enjoy this a lot. In particular there’s some extemporaneous instrumental starting at around 8 minutes, in which there’s a bit of flute work which may well have inspired Lady Gaga’s ubiquitous pop hit “Poker Face”.

The next one I will highlight is from New York indie folk rockers The Maledictions. It’s basically a large dose of Nick Cave’s “Stagger Lee” infused with the story of Jellon Grame. PARENT ADVISORY. Contains quite a lot of very adult language towards the end. Sorry if you’re not up for that sort of thing. If you are: enjoy.

Finally, a relatively recent Americanisation of the ballad appeared in 2007, from US traditional singer Bob Coltman who at the ripe old age of 70 (proving you are never too old to tinker with the oral tradition) reworked Jellon Grame in an Appalachian style, complete with refrain. He may have been inspired by the 1956 Paul Clayton version, as Coltman wrote a detailed biography of Clayton in 1976 for a publication called Old Time Music, later turning it into a book in 2008.

Sir Walter Scott’s analysis

As usual with plenty of largely fruitless speculation as to the ballad’s origins.

(from Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border by Sir Walter Scott)

Appalachian mountain women and Jellon Grame

This article contains the following passage, looking at the purpose of murder ballads, including Jellon Grame, in the sexual politics of Southern Appalachia.

Supernatural elements of Jellon Grame: preternatural growth, and infertile ground

Most of the ballad is bleakly plausible, but some versions do make reference to supernatural goings-on. This is handily summarised in the short passage and footnote from the excellent “Death and Burial Lore in the English and Scottish Popular Ballads” by Lowry Charles Wimberley.

The passage above also includes a reference to Child’s Additions and corrections which includes the following note regarding ballads around the world that refer to precocious growth.

Precocious growth.

The French romance of Alexander. Albéric de Besançon: Alexander had more strength when three days old than other children of four months; he walked and ran better from his first year than any other child from its seventh. (The same, nearly, in Lamprecht, vv. 142-4: he throve better in three days than any other child of three months; 178-80, in his first year his strength and body waxed more than another's in three.) Manuscript de l'Arsenal: the child grew in vitality and knowledge more in seven years than others do in a hundred. Manuscript de Venise: he grew more in body and knowledge in eight years than others in a hundred. P. Meyer, Alexandre le Grand, I, 5, v. 56 f., 6, v. 74 f., 27, v. 39 f., 240, v. 53 f. 'Plus sot en x jors que i. autres en c:' Michelant, p. 8, v. 20. A similar precocity is recorded of the Chinese Emperor Schimong: Gützlaff, Geschichte der Chinesen, hrsgg. v. Neumann, S. 19, cited by Weismann, Lamprecht's Alexander, I, 432.

In the romance of Mélusine it is related how, after her disappearance in serpent-form, she was seen by the nurses to return at night and care for her two infant sons, who, according to the earliest version, the prose of Jehan d'Arras, grew more in a week than other children in a month: ed. Brunet, 1854, p. 361. The same in the French romance, I. 4347 f., the English metrical version, I. 4035-37, and in the German Volksbuch. (H. L. Koopman.)

Tom Hickathrift "was in length, when he was but ten years of age, about eight foot, and in thickness five foot, and his hand was like unto a shoulder of mutton, and in all parts from top to toe he was like a monster." The History of Thomas Hickathrift, ed. by G.L. Gomme, Villon Society, 1885, p. 2. (G. L. K.)

And also:

Vol'ga, Volch, of the Russian bylinas, must have a high place among the precocious heroes. When he was an hour and a half old his voice was like thunder, and at five years of age he made the earth tremble under his tread. At seven he had learned all cunning and wisdom, and all the languages. Dobrynya is also to be mentioned. See Wollner, Volksepik der Grossrussen, pp. 47 f., 91.

Simon the Foundling in the fine Servian heroic song of that name, Karadzic, II, 63, No 14, Talvj, I, 71, when he is a year old is like other children of three; when he is twelve like others of twenty, and wonderfully learned, with no occasion to be afraid of any scholar, not even the abbot. (Cf. 'The Lord of Lorne,' V, 54, 9, 10.)

The other magical element of the ballad mentioned in Wimberley above is the description of a patch of ground where nothing will grow marking the place where the murdered woman fell:

“How all this wood is growing grass,

And on this small spot grows none?”

This idea of the ground being cursed into infertility due to some unjust death is common and international. One example is Texas-born Marion “Peg-Leg” Brown who was send to the gallows for murder in Ontario, in May 1899. There were question marks over the largely circumstantial evidence, and the fact his grave remained bare is a supernatural testimony to his innocence. This is worth reading to the end - the author asserts (I think jokingly) that *still* nothing grows on his grave. Mainly due to the fact it was paved over for a car park in 1985.

There is another example very near where I currently live.

On 16th July 1923, William Wood, a weaver from Eyam, was walking the 30 miles home from Manchester after selling his cloth. He had stopped in an alehouse for refreshments somewhere around Disley or High Lane, and was walking over the hill on the Buxton Old Road towards Whaley Bridge, when he was attacked by three men dressed as sailors, and robbed, his body left for dead at the side of the road. It’s said they had crushed his head with a coping stone from a nearby wall. Local accounts state that there was a hole where Wood's lifeless and bloody head lay, and that hole could never be filled, nor would anything grow in it.

I took a photo of the commemorative stone about 15 years ago. I don’t think I have walked that way since, I must go and see if there are any bare patches of ground nearby.

You can read more about William Wood and the intriguing murder case that followed here, over 10 meticulously researched pages.

Draft pages and audio guide

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.