ROUD 56: Young Johnstone

AKA: Young Johnston, Young Johnson, Lord John's Murder, William and the Young Colonel, The Cruel Knight

(Quick bit of housekeeping: I have realised six ballads into this process that I can combine both unpaid and premium content in one email. This bit should be available to everyone, and the bottom bit only to paid subscribers. Hopefully this works, and will clog up your email accounts slightly less! Please let me know if you’re having problems. OK, on with the show.)

Another ballad that while popular in the 19th century, is rarely performed now. Possibly due to the confusingly presented setup to the story; it took me a few reads to figure out whose sister was being impugned. Still, the research took me down some interesting side-roads, including archaic Scottish door-furniture and Serbian wine-drinking.

Music

In addition, the website Tobhar an Dualchais has a number of recordings from the 1970s to the 1980s. (Thanks to the brilliant Alasdair Roberts for alerting me to this superb resource.)

The Mainly Norfolk entry for the ballad lists a couple of other recordings that are hard to find, but it looks like they are all based on Betsy Whyte’s melody.

The Johnstones

Betsy White, from whose singing most contemporary versions of the ballad derive, delivers a long discussion of the history of the song, in which she is absolutely insistent that it is a true story. You can hear the full discussion on this 1974 recording:

The Clan Johnstone were certainly a real family of border reivers and outlaws, known for their murderous implulsiveness, which would certainly tally with the exploits of Johnstone in this ballad. The family’s exploits are recorded in two other ballads, The Lads of Wamphray and Lord Maxwell’s Goodnight. A number of Johnstone family members have had Young Johnstone collected from them: Duncan Johnstone of Birnam in 1967 when in his 80s, his niece Margaret Johnstone recorded in Fife in 1968, another niece Betsy White herself (nee Johnstone) and also from Betsy's sister in Australia, making it something of a “family song”.

Johnstone’s murderous motivation

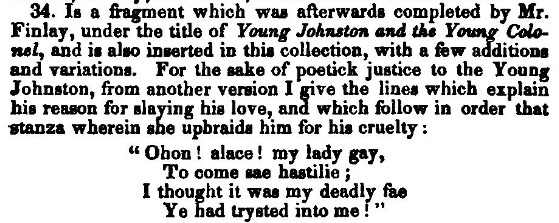

There are multiple mentions of this in ballad literature, usually cited as an example of the unexplained motives shown in traditional song. Motherwell claims to have recorded from a reciter that Johnstone was simply drunk and confused to be roused from his slumber, and killed his lover by mistake, which is also the implication in the version collected by Peter Buchan sometime around 1820. Although there is another possibility: that there is a class motive (that the other man’s sister is not fit to wed, but only to be taken as a mistress) and the murder an act of inter-class revenge.

From Motherwell:

Tirling at the pin

Many longer versions (ie. not the one in Sing Yonder) contain a phrase that turns up in a number of old Scottish ballads, namely the action performed at the door of Johnstone’s mother/sister/lover, “tirling at the pin”, or sometimes “tinkling at the ring”.

Then he's away to his sister's bower,

He's tirled at the pin:

This refers to the tirling pin, a kind of proto-doorbell that was commonly found (and still occasionally found) in Scotland and Northern England - an account here:

(from “Ancient Meols: or, Some account of the antiquities found near Dove Point” (1863), by Abraham Hume.), and another here, using the more decorous term “risp and ringle”:

Further, from musicologist Dr Christopher Smith (@ChrisSmithMuso on Twitter) comes this:

My mentor and friend Henry Glassie has a wonderful long exegesis in his masterpiece PASSING THE TIME IN BALLYMENONE about door-knocker design, about how they were designed to be rattled--not locked--b/c to "knock" on a neighbor's door, indirectly, implied that one needed an invitation to enter. That would, indirectly, impugn neighbor's hospitality--so instead, you simply "rattled the latch" (to let them know there was a visitor) & then walked into the kitchen--the center of the house.

This idea of the social derivation of the tirling pin is borne out by the article on Wikipedia, which also explains that the use of the phrase in the more ancient ballads could predate the invention of the door hardware, and be referring to the act of rattling the latch, as described above. Although it seems likely that the sometimes used “tinkling of the ring” version does refer to the noise-making ironmongery, an image of which is shown below:

Wine drinking in Serbian balladry

Young Johnstone gets a mention in this passage from “Popular culture in early modern Europe” (1978) by Peter Burke.

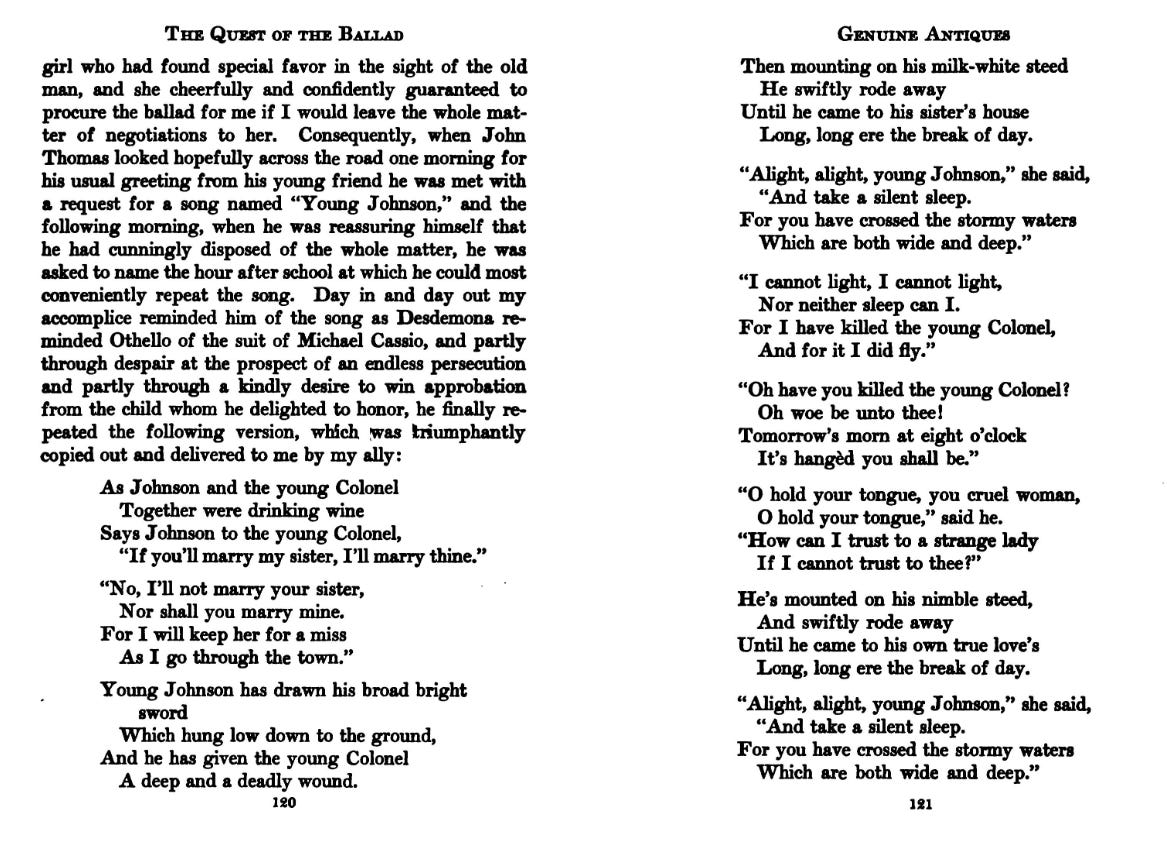

William Roy Mackenzie finds the ballad in Nova Scotia

“The Quest of the Ballad” is the compelling 1919 account of folk song collecting from Canadian scholar William Roy Mackenzie. It includes this amusing anecdote about his attempts to wrest a version of Young Johnstone from a not-entirely-cooperative singer by the name of John Thomas Matheson. If you don’t want to read the whole thing (and it is worth doing - Mackenzie’s plan for motivating the procrastinating balladeer is, er, somewhat “retro” - possibly in a charming way, and possibly highly disturbing, depending on your level of cynicism), this is the standout quote:

John Thomas was a procrastinator, not of the domestic garden variety, but of a rare and splendid orchid-like species hard to find even in this world of delays. He was, to speak allegorically, procrastination itself personified and incarnate.

… and then describes how Matheson always starts an unrelated job at a time when he knows he will definitely have to stop before the job is finished, and which will also preclude him from doing the things he has committed to do.

The whole book is available to read on the always indispensable Archive.org.

Draft pages and audio guide

My stab at summarizing all of the above, and probably some other stuff as well, is given below for paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sing Yonder: A Practical Guide to Traditional Song to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.