ROUD 55: Lord Abore and Mary Flynn

AKA: Prince Robert, Earl Robert, Lord Robert and Mary Florence, Lord O'Bore, Harry Saunders

Really fell in love with this one. A great tune and a story full of tragedy and intrigue. Thought at one time to be lost to the tradition, it resurfaced in Ireland in the 1960s, in a beautiful example of the immeasurable value of the oral folk tradition. The melody that accompanied that 1960s revival is a really lovely one to sing, and deserves more recorded versions, IMO.

Music

Here’s the Youtube playlist. One of those rare instances where everything on Mainly Norfolk is easily available, plus some extra stuff that hasn’t yet crossed Reinhardt’s radar.

Also there is a superb episode of the brilliant Fire Draw Near podcast from Ian Lynch dedicated to this rarely played ballad - it’s clearly a song that caught his imagination too. On Ian’s podcast you can hear a difficult-to-find Appalachian version from Peggy seeger, and a fantastic and very revealing little anecdote from the Dublin pub session in which Ian sings - I could recount it here, but I recommend you listen to the podcast, as Ian tells it better.

Sources

This page has a nice account (from the sleevenotes of Al O’Donnell’s album) of how Tom Munnelly was “thunderstruck” when hearing the ballad played out in a Dublin pub.

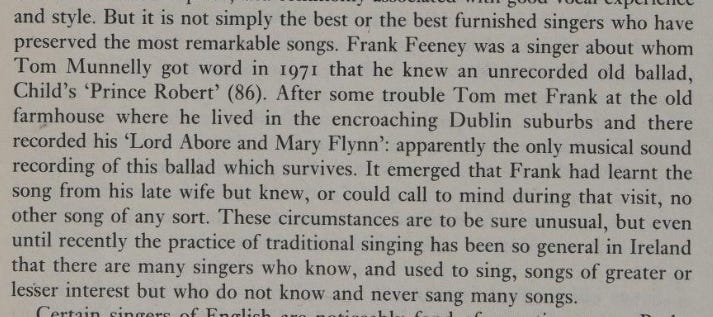

Source: Al O'Donnell 'Al O'Donnell 2' The Leader Tradition LTRA 501. Tom Munnelly collated this text from recordings of Jim Kelly and Frank Feeney and passed it on to Al O'Donnell. This is a lovely Irish version of Child ballad 87 'Prince Robert', a Scots version of which is to be found in the DT. Tom Munnelly noted: 'This spendid ballad of a mother who poisons her son to prevent his marriage Professor Child included in his monumental collection as No 87 'Prince Robert'. The four versions he publishes are all of Scots origin, but unfortunately the tune was never noted by the collectors. As all these texts were early 19th century, the ballad was thought to be traditionally extinct. This being the case, you can imagine how thunderstruck I was when I heard it being sung in a Dublin pub in 1969! The singer was Jim Kelly who learned it from Frank Feeney who in turn had it from his late wife, a Carlow woman'. (Tom Munnelly notes to LTRA 501) If you compare Stewie's Lord Abore and Mary Flynn above with "Prince Robert" from the Digital Tradition (DT) you cannot easily spot the similariti The similarities are weaker in other verses, but Child 87, version C, is the precursor of the ballad above. And if you listen closely in your mind to someone singing the words 'Lord Robert' with the stress on the last syllable of the name (as the tune I know demands), you can hear how 'Abore' is but a mondegreen of 'Robert'.

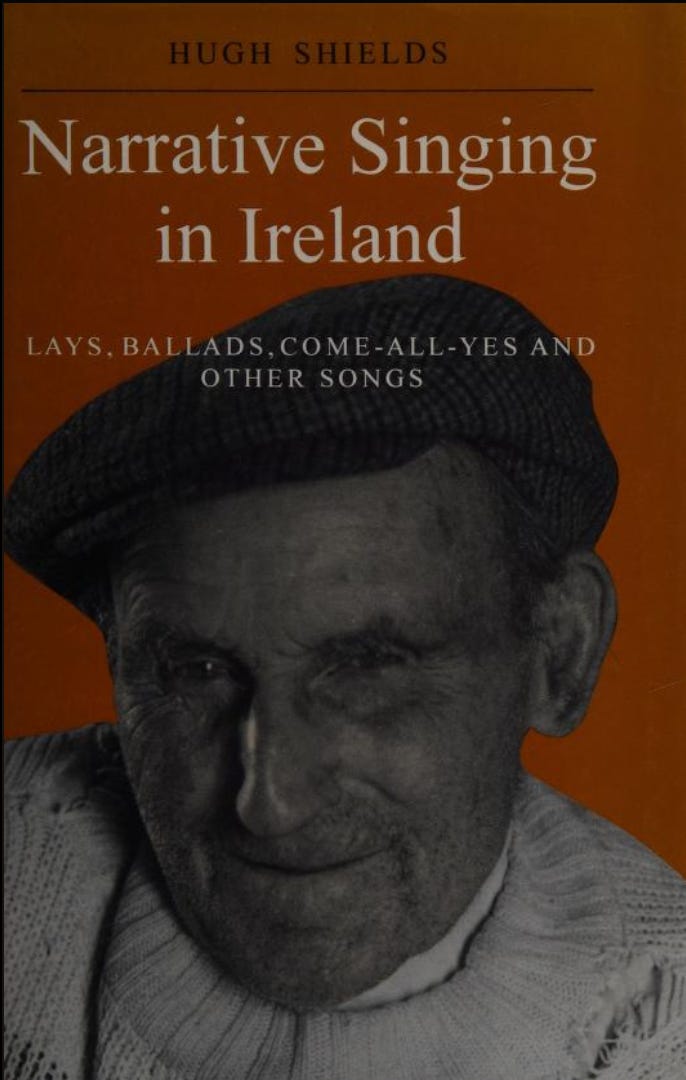

A lot of the discussion around the Irish revival stems from the fantastic work of Irish traditional music scholar Hugh Shields. His book “Narrative Singing in Ireland” has several mentions of this ballad, and is full of interesting accounts of Irish ballad singing in the wild.

and here’s an example:

Another great source of Irish balladry is the album, Early Ballads in Ireland reviewed here. The review contains this useful info about the early recordings from which the versions we here today are derived:

Lord Abore, a Child ballad (87, Prince Robert a tale of young love fatally thwarted by a disapproving mother and a flask of poison), previously invisible in oral tradition and unrepresented in Bronson, yet here we have two versions coming along at once, like those buses that appear in convoy after a long wait. Not exactly separate variants, since Jim Kelly, the first performer, learned the song from Frank Feeney, the second. They're not identical, though. Both are well-paced, lyrical performances but, where Kelly's follows the 4:4 rhythm very steadily, Feeney's lingers over the refrain and hurries into the following verse, so the tapping foot is deceived. Perhaps Kelly, the younger man by nearly forty years, was more influenced by the regular beat of recorded music. There are other, more substantial, differences, too: the tune is altered slightly in the second phrase, and there are several textual changes. Some are simple substitutions in vocabulary ('cask' for 'bottle' of wine, or steed' for 'horse') while another provides a rhyme where there was none before. Most notably, Kelly's is missing two of Feeney's verses - concerning the striking account of the ring that 'spilt in three' - but includes another, absent from the Feeney version. It's impossible to guess whether the changes are Kelly's, conscious or unconscious, or whether Feeney's own performance had changed between the passing down of the song, and the arrival of Munnelly's tape machine. Either way it's an interesting illustration of how a song can evolve even at just one remove.

Sometimes it’s interesting to look at place names in ballads - in the oft-performed “big” ballads you will sometimes have certain locations reappearing then changing over time and locale, like bubbles in a pool, often influenced by the singer’s need to identify a ballad with their own surroundings. With a rare ballad like this, however, just a couple of places appear, and there’s very little mention of it in ballad scholarship. All I found was this brief mention of “Sillertoun” in one of the original versions taken from Scott’s Border Minstrelsy. This version is reproduced in “The history and antiquities of the parish of Darlington, in the bishoprick” (1854) by William Hylton Longstaffe, with the following note:

“Sittengen’s Rocks” is not a named location on any map, but, living in an area well populated with stony outcrops, I know that many local names for these places are not documented other than in the colloquial speech of the local people.

Robert of Huntingdon?

It’s an always fun (and almost always fruitless) game to play “Link the Historical Figure to the Traditional Song”. If an actual Royal Prince had been victim of poisoning at the hands of his own mother, we might have heard of that. However, one of the alternate titles of the ballad “Earl Robert” yields a possible connection. David of Scotland was a Scottish prince and the 8th Earl of Huntingdon. He had seven children with his wife Matilda of Cheshire. We know little about the family, as they were around in the late 12th century and record keeping in those times is notoriously patchy, but we do know their second child died young, and his name was Robert. No records show that he was poisoned by Matilda for an unsuitable love match. Interestingly, Robert Fitzooth (or Fitztooth), Earl of Huntingdon is the name used as the fictitious identity of a certain Robin Hood, a popular hero of many (approximately 14% in fact) Child ballads. Anyway, here’s a picture of David, Earl of Huntingdon.